JULY 16th.—The Secretary was back again this evening. He could not procure comfortable quarters in the country. He seemed vexed, but from what cause, I did not learn. The colonel, however, had rushed the appointments. He was determined to be quick, because Mr. W. was known to be slow and hesitating.

American Civil War Chronicles

Virginia!

July 16, 2021

Extracts from the journal of Commander Semmes, C.S. Navy, commanding C.S.S. Sumter

July 16, 2021

Mary Chesnut’s diary.—”As far as I can make out, Beauregard sent Mr. Chesnut to the President to gain permission for the forces of Joe Johnston and Beauregard to join, and, united, to push the enemy, if possible, over the Potomac…”

July 16, 2021

July 16th.–Dined to-day at the President’s table. Joe Davis, the nephew, asked me if I liked white port wine. I said I did not know; “all that I had ever known had been dark red.” So he poured me out a glass. I drank it, and it nearly burned up my mouth and throat. It was horrid, but I did not let him see how it annoyed me. I pretended to be glad that any one found me still young enough to play off a practical joke upon me. It was thirty years since I had thought of such a thing.

Met Colonel Baldwin in the drawing-room. He pointed significantly to his Confederate colonel’s buttons and gray coat. At the White Sulphur last summer he was a “Union man” to the last point. “How much have you changed besides your coat?” “I was always true to our country,” he said. “She leaves me no choice now.”

As far as I can make out, Beauregard sent Mr. Chesnut to the President to gain permission for the forces of Joe Johnston and Beauregard to join, and, united, to push the enemy, if possible, over the Potomac. Now every day we grow weaker and they stronger; so we had better give a telling blow at once. Already, we begin to cry out for more ammunition, and already the blockade is beginning to shut it all out.

A young Emory is here. His mother writes him to go back. Her Franklin blood certainly calls him with no uncertain sound to the Northern side, while his fatherland is wavering and undecided, split in half by factions. Mrs. Wigfall says he is half inclined to go. She wondered that he did not. With a father in the enemy’s army, he will always be “suspect” here, let the President and Mrs. Davis do for him what they will.

I did not know there was such a “bitter cry” left in me, but I wept my heart away to-day when my husband went off. Things do look so black. When he comes up here he rarely brings his body-servant, a negro man. Lawrence has charge of all Mr. Chesnut’s things–watch, clothes, and two or three hundred gold pieces that lie in the tray of his trunk. All these, papers, etc., he tells Lawrence to bring to me if anything happens to him. But I said: “Maybe he will pack off to the Yankees and freedom with all that.” “Fiddlesticks! He is not going to leave me for anybody else. After all, what can he ever be, better than he is now–a gentleman’s gentleman?” “He is within sound of the enemy’s guns, and when he gets to the other army he is free.” Maria said of Mr. Preston’s man: “What he want with anything more, ef he was free? Don’t he live just as well as Mars John do now?”

Mrs. McLane, Mrs. Joe Johnston, Mrs. Wigall, all came. I am sure so many clever women could divert a soul in extremis. The Hampton Legion all in a snarl–about, I forget what; standing on their dignity, I suppose. I have come to detest a man who says, “My own personal dignity and self-respect require.” I long to cry, “No need to respect yourself until you can make other people do it.”

William Howard Russell’s Diary: The “State House” at Annapolis.—Washington.

July 16, 2021

July 19th. (probably 16th, based on sequence in book and events)–I baffled many curious and civil citizens by breakfasting in my room, where I remained writing till late in the day. In the afternoon I walked to the State House. The hall door was open, but the rooms were closed; and I remained in the hall, which is graced by two indifferent huge statues of Law and Justice holding gas lamps, and by an old rusty cannon, dug out of the river, and supposed to have belonged to the original British colonists, whilst an officer whom I met in the portico went to look for the porter and the keys. Whether he succeeded I cannot say, for after waiting some half hour I was warned by my watch that it was time to get ready for the train, which started at 4 ·15 P.M.. The country through which the single line of rail passes is very hilly, much wooded, little cultivated, cut up by water-courses and ravines. At the junction with the Washington line from Baltimore there is a strong guard thrown out from the camp near at hand. The officers, who had a mess in a little wayside inn on the line, invited me to rest till the train came up, and from them I heard that an advance had been actually ordered, and that if the “rebels” stood there would soon be a tall fight close to Washington. They were very cheery, hospitable fellows, and enjoyed their new mode of life amazingly. The men of the regiment to which they belonged were Germans, almost to a man. When the train came in I found it was full of soldiers, and I learned that three more heavy trains were to follow, in addition to four which had already passed laden with troops.

On arriving at the Washington platform, the first person I saw was General M’Dowell alone, looking anxiously into the carriages. He asked where I came from, and when he heard from Annapolis, inquired eagerly if I had seen two batteries of artillery– Barry’s and another–which he had ordered up, and was waiting for, but which had “gone astray.” I was surprised to find the General engaged on such duty, and took leave to say so. “Well, it is quite true, Mr. Russell; but I am obliged to look after them myself, as I have so small a staff, and they are all engaged out with my head-quarters. You are aware I have advanced? No! Well, you have just come in time, and I shall be happy, indeed, to take you with me. I have made arrangements for the correspondents of our papers to take the field under certain regulations, and I have suggested to them they should wear a white uniform, to indicate the purity of their character.” The General could hear nothing of his guns; his carriage was waiting, and I accepted his offer of a seat to my lodgings. Although he spoke confidently, he did not seem in good spirits. There was the greatest difficulty in finding out anything about the enemy. Beauregard was said to have advanced to Fairfax Court House, but he could not get any certain knowledge of the fact. “Can you not order a reconnaissance?” “Wait till you see the country. But even if it were as flat as Flanders, I have not an officer on whom I could depend for the work. They would fall into some trap, or bring on a general engagement when I did not seek it or desire it. I have no cavalry such as you work with in Europe.” I think he was not so much disposed to undervalue the Confederates as before, for he said they had selected a very strong position, and had made a regular levée en masse of the people of Virginia, as a proof of the energy and determination with which they were entering on the campaign.

As we parted the General gave me his photograph, and told me he expected to see me in a few days at his quarters, but that I would have plenty of time to get horses and servants, and such light equipage as I wanted, as there would be no engagement for several days. On arriving at my lodgings I sent to the livery stables to inquire after horses. None fit for the saddle to be had at any price. The sutlers, the cavalry, the mounted officers, had been purchasing up all the droves of horses which came to the markets. M’Dowell had barely extra mounts for his own use. And yet horses must be had; and, even provided with them, I must take the field without tent or servant, canteen or food–a waif to fortune.

A Diary of American Events – July 16, 1861

July 16, 2021

July 16.–The Union troops in Missouri had a fight with the rebels to-day, at a point called Millsville, on the North Missouri Railroad. The Union troops, consisting of eight hundred men, were fired into at that point, as they came up in a train of cars, and an engagement at once ensued. The number of the rebels is not known, but seven of their number were killed and several taken prisoners.–N. Y. Herald, July 18.

–The Third Massachusetts Regiment sails from Fortress Monroe for Boston this evening in the steamer Cambridge. They were reviewed by General Butler to-day.–The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment follows to-morrow.–Col. Max Leber’s and Col. Baker’s Regiments were to occupy Hampton, but the plan has been somewhat changed.–Brigadier-General Pierce returns with the Massachusetts Regiments.–Col. Duryea will be acting Brigadier General in Hampton.–Several companies went out from Newport News last night to surprise, if possible, a body of light horse, which have for some time hovered in the vicinity.–National Intelligencer, July 18.

–In the House of Representatives at Washington, the Committee on Commerce, in response to a resolution directing inquiry as to what measures are necessary to suppress privateering, and render the blockade of the rebel ports more effectual, reported a bill authorizing the Secretary of the Navy to hire, purchase, or contract for such vessels as may be necessary for a temporary increase of the navy, the vessels to be furnished with such ordnance, stores, and munitions of war as will enable them to render the most efficient service. According to the orders issued to their respective commands, the temporary appointments made of acting lieutenants, acting paymasters, acting surgeons, masters and masters’ mates, and the rates of pay for these officers heretofore designed, are, by this bill, legalized and approved.

For the purpose of carrying this act into effect to suppress piracy and render the blockade more effectual, three millions of dollars are appropriated. The bill was referred to the Committee on Naval Affairs.–A bill, authorizing the President to call out the militia to suppress rebellion, was passed unanimously.–The bill, authorizing the President to accept the services of five hundred thousand volunteers, was also passed.–The Senate’s amendments to the Loan bill were all concurred in.–A joint resolution, conveying the thanks of Congress to Major General George B. McClellan and the officers and soldiers under his command, for the recent brilliant victories over the rebels in Western Virginia, was unanimously adopted.

–Lieut. W. H. Free, of the Seventh Ohio Regiment, from a company enlisted in Perry County, Ohio, arrived at Columbus in that State with four Secessionists. Free, with twenty-five men, was conducting a transportation train from Ravenswood, Virginia, to Parkersburg. On Sunday last, he stopped at a farm-house to bait the horses. He immediately found that the women of the house sympathized with Secession. The farmer was absent. Thinking he might learn some facts of importance, ho assured the women that he was an officer from Wise’s brigade. At first they distrusted him, but at length gave him their confidence, and treated him very kindly. He learned that the farmer would be at home at night. About ten o’clock he came. Free soon gained his confidence, and was told that a meeting had been arranged at a neighboring house for the purpose of planning an attack upon Union men. Free pretending to need a guide to show him the way to Wise’s camp, the farmer, named Fred. Kizer, sent for some of his neighbors. Three of them came, one of whom was recommended as a guide. Free became satisfied from their conversation that they intended harm to Coleman and Smith, Union men, who had been influential, and at a concerted signal called his men around him, and declared himself an officer of the United States army. Instantly Kizer and his rebel friends were seized. The Lieutenant immediately ordered a march, and the next morning delivered his prisoners to Captain Stinchcomb, at Parkersburg, who sent him with three guards to Columbus. The names of the prisoners are Frederick Kizer, David H. Young, John W. Wigal, and John H. Lockwood.–Cincinnati Gazette, July 17.

–In the Senate of the United States, John 0. Breckenridge, of Kentucky, in an elaborate speech, opposed the resolution approving the acts of the President in suppressing the Southern rebellion. He rehearsed the old arguments against the right of the Government to put down rebellion, and in the course of his remarks, took occasion to deny positively that he had ever telegraphed to Jeff. Davis that President Lincoln’s Congress would not be allowed to meet in Washington on the 4th of July, or that Kentucky would furnish 7,000 armed men for the rebel army.–(Doc. 94.)

–It is doubtful, says the National Intelligencer of this date, whether, since the days of Peter the Hermit, the world has seen such an uprising, at the bidding of a sentiment, as this country has exhibited in the last ninety days. Perhaps the magnitude of the effort is best appreciated by observing what has been done by single States of the Confederacy. And to illustrate this, we need not even adduce the exertions of sovereignties dating back to Revolutionary days, as New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Younger members of the Confederacy, States that half a century since had no existence, contribute singly no inconsiderable army to the assembling forces of the Union. Let us instance one of these, which recent events in Western Virginia have brought favorably and prominently forward–Indiana, forty-five years ago a frontier Territory, where the red man still contended with the white pioneer. Indiana has equipped, and is equipping for the General Government, a force such as has decided ere now the fate of a nation–twenty-three regiments, a volunteer army of more than twenty thousand infantry and twelve hundred cavalry; and these she has not only uniformed and accoutred, but partially armed with the improved rifle of the day, meanwhile at her own expense.

This is no isolated example. Others have done as well. If the power of a sentiment is to be estimated by the deeds it prompts, how strong must be the love of the Union in the hearts of its citizens!

–The Federal army in Virginia to-day took up the line of march for Fairfax and Manassas. The force standing to-day is fully 60,000 strong, the number reaching by actual count about 68,000. These are about 3,000 regular infantry, cavalry, and artillery, and 50,000 volunteers. The two Rhode Island, the 71st New York, and the 2d New Hampshire, comprising Colonel Burnside’s brigade, left Washington at 4 o’clock this afternoon, and struck the road for Fairfax Court House. The 27th New York went over at 6 o’clock, and also took the Fairfax route. As soon as these regiments came together and passed the encampment, the soldiers cheered lustily and shouted congratulations to each other that they were fairly on the road to the rebel capital. The Dekalb Regiment passed over the bridge and went into Camp Runyon.–(Doc. 97.)

Civil War Day-By-Day

July 16, 2021

July 16, 1861

- At the order of President Abraham Lincoln, Union troops begin a 25-mile march into Virginia for what will become the First Battle of Bull Run, the first major land battle of the war.

A Chronological History of the Civil War in America1

- Rebel pickets driven beyond Fairfax Court House,Va.

- Battle at Barboursville, Va.; rebels defeated.

- Tighlman, a negro, killed three of the rebel prize crew on the schooner “S. J. Waring,” and brought the vessel into New York.

- Skirmish at Millville, Mo.

- A Chronological History of the Civil War in America by Richard Swainson Fisher, New York, Johnson and Ward, 1863

“Was at the Camp with the officers of the Lyons Co. Their Regt is expecting orders to march.—Horatio Nelson Taft

July 15, 2021

MONDAY, JULY 15, 1861.

Nothing in particular has occured today, excepting the arrival of a number of Regts from the North and the passage of a number over the River into Virginia. Crowds visit the patent office every day. The City is very full now of strangers as well as soldiers. The latter are mostly in Camp back of the City. Saw the “Union” Regt practice firing at target this afternoon. Was at the Camp with the officers of the Lyons Co. Am home this evening. Their Regt is expecting orders to march.

______

The three diary manuscript volumes, Washington during the Civil War: The Diary of Horatio Nelson Taft, 1861-1865, are available online at The Library of Congress.

Rebel War Clerk.—More War Office petty politics.

July 15, 2021

JULY 15th.—Early this morning, Major Tyler was seated in the Secretary’s chair, prepared to receive the visitors. This, I suppose, was of course in pursuance of the Secretary’s request; and accordingly the door-keeper ushered in the people. But not long after Col. Bledsoe arrived, and exhibited to me an order from the President for him to act as Secretary of War pro tem. The colonel was in high spirits, and full dress; and seemed in no measure piqued at Major Tyler for occupying the Secretary’s chair. The Secretary must have been aware that the colonel was to act during his absence—but, probably, supposed it proper that the major, from his suavity of manners, was best qualified for the reception of the visitors. He had been longer in the department, and was more familiar with the routine of business. Yet the colonel was not satisfied; and accordingly requested me to intimate the fact to Major Tyler, of which, it seemed, he had no previous information, that the President had appointed Col. Bledsoe to act as Secretary of War during the absence of Mr. Walker. The major retired from the office immediately, relinquishing his post with grace.

“Get ready for a forward movement.”

July 15, 2021

Extracts from the journal of Commander Semmes, C.S. Navy, commanding C.S.S. Sumter

July 15, 2021

“Who wouldn’t be a nuss”—Woolsey family letters, Harriet Roosevelt Woolsey to Georgeanna and Eliza.

July 15, 2021

New York, Monday, July 15, 1861.

My dear Girls: I might as well give you the benefit of a scrawl just to thank you for the big yellow envelope in Georgy’s handwriting lying on the library table by me. It has just come and I think you are two of the luckiest fellows living to be where you are, down in the very thick of it all, with war secrets going on in the next tent and telegraph-wires twitching with important dispatches just outside of your door. “Who wouldn’t be a nuss” under such circumstances? or would you prefer staying at home to arrange flowers, entertain P. in the evenings, devise a trimming for the dress Gonden is making for you, and go off into the country to fold your hands and do nothing? I tell you, Georgy, you are a happy creature and ought to be thankful. Jane and Abby have been in Astoria all the week. It was a triumph of ours to make Abby loosen her hold of those abominable old women of the widow’s society. She won’t get back to them for some time either. . . . Mother and I went up to Northampton, Mass., one evening last week to look up summer quarters. We went via New Haven by the 11 o’clock boat. Charley saw us on board and we got to bed about twelve. Quite a good night for a boat. Mother says she slept well, and was prime for a walk over to the depot before breakfast the next morning. She is certainly made of more enduring material than the rest of us, and, after getting through our business, wanted to come back in the express train at 5.30 that evening. Mr. Frank Bond and Mr. Thomas Denny spent the other evening here. F. B. is going on to Washington very soon, and is to be with General Tyler, something or other to him, and charged me when I wrote to let you know he was coming, and renewed his invitation to you to accompany them into Virginia as chief surgeon!

Mary has cut Bertha’s hair square across her forehead, which makes her look more sinful and unregenerate than ever. Polly has had her’s cut, and is more comfortable. Did Robert mention the box of old wine for General Scott, from Uncle E.? Think how glorious a part to take–propping up the government with rare old wine from one’s own cellar.”

“…there is not a soul here that cares whether I go or stay, or that I could call a friend;”

July 15, 2021

(excerpts)

“July 15th, Longwood, near Boston.

“. . . I received your last letter several days ago, and I had a letter from Mama about the same time, telling Grandmama to send us on by the first good opportunity, but the way Mr. Walters said was the only way we could go would not have been safe, and I am now anxiously awaiting news from Mama as to whether we shall go to Fortress Monroe, and let Papa send a flag of truce, and get us or not. My trunks were all packed ready to start at a minute’s notice, when we received Mr. Walter’s letter, telling us that the only way of reaching Richmond was by going through Winchester, to which you know the troops are making a general movement.

“You may imagine how I felt. When Mr. Walters wrote the last time, all was different, and I fully expected to go home. I had already pictured our meeting. I almost felt your kiss and I heard Papa calling us ‘his darlings’ and Mama’s dear voice, and in one moment all was gone, and I glanced out of my window and instead of Richmond, I saw miserable old Boston. I felt as if my heart would break.

“You ask me in your last if I am not ‘isolated’ – that is exactly the word. With the exception of Emma Babcock, and her family, there is not a soul here that cares whether I go or stay, or that I could call a friend; but if nobody likes me, there is some satisfaction in knowing there is no love lost. If I did not follow your injunction, and never believe what I see in Republican journals I should have an awful time of it; for they make out the most desperate case. All the C. S. soldiers are poor, half starved, naked, miserable wretches that will run if you stick your finger at them; who are all waiting for a chance to desert, etc., and become loyal citizens to King Abraham, the First, and prime minister, General Scott. The Southerners are defeated in every engagement; all the killed and wounded are on their side, and none are injured on the other. Such is about the summary of their statements— mais je ne le crois pas, and so they don’t disturb my mind much. I saw that Papa had gone disguised as a cattle drover to Washington, to pick up information for the President! That is about a specimen of their stories. Mama writes me in her last that you have joined the Military School at the University of Virginia, and would enter the army in three months, if you wished to, at the end of that time. I suppose you are very glad. I don’t wonder and wish I could go too. I sit down to the piano every day and play ‘Dixie’ and think of you all away in ‘the land ob cotton,’ etc.”

Commissioned Officers of the Second Regiment Iowa Volunteers petition that the Hon Samuel R. Curtis be appointed theirBrigadier General

July 15, 2021

To Abraham Lincoln President of the United States of America Greeting

We your petitioners, Commissioned Officers of the Second Regiment Iowa Volunteers, would most Respectfully beg leave to Express our desire, as well as the wishes of our respective Commands by them unanimously expressed, that the Hon Samuel R. Curtis be appointed our Brigadier General. Believing him to be eminently qualified as a man of ability, Cool Judgment and Discretion, Military education and Experience, to Command as such, and believing the Service would be benefited by the Appointment we would therefore most respectfully beg his appointment to the office of Brigadier General and that he Command us as such.

Hoping it may please you to Grant the prayers of your petitioners we subscribe our selves you most obedient

M. M. Crocker Maj 2nd Reg Iowa Volunteers

J. M. Tuttle Lt. Col 2d Iowa Reg

N. P. Chipman Adjt 2d Reg’t Iowa Vols.

W. R. Marsh Surgeon 2d Reg la Vol

R. H. Huston Capt Co. A

F. I. McKenny 1st Lieut Co A.

S. M. Archer 2nd Lieut Co. A.

W. W. Nassau–Asst Surgeon 2 Reg. la V.

J. D. _____ Capt Co “C” 2d Iowa Regt

J. S. Slaymaker 1st Lt. Comp “C”

W. F. Holmes 2 ” ” ”

N. W. Mills, Capt. Co. D.

E. T. Ensign 2d Lieut Co D

Frederick F. Metzler, Captn Co E 2nd Reg’t Iowa Vol’s

John T. McCullough 2nd Lieu. Co. E 2nd Reg

A. T. Brooks Capt. Comp F

R. M. Littler Capt Co B 2 Reg

J. G. Huntington 1st Lieut Co. B 2 Reg

Jno Flanagan 2nd Lieut ” ” ” ”

S. H. Lunt 1st Lieut Co D 2nd Reg

James Baker Capt. Co. G.

Samuel A. Moore 2d Lieut Co. G

Hugh T. Cox Captn Comp. J

N. B. Howard, 1st Lieut

Thomas R. Snowden 2d Lieut

Alonzo Eaton 1 Lieut Co K

J. B. Weaver lst Lieut Co G.

A. T. Brooks Capt. Co. F. [name repeated, see above]

Abe Wilkin 1st Lieut Co F

William Howard Russell’s Diary: A voyage by steamer to Annapolis.

July 15, 2021

July 15th.–I need not speak much of the events of last night, which were not unimportant, perhaps, to some of the insects which played a leading part in them. The heat was literally overpowering; for in addition to the hot night there was the full power of most irritable boilers close at hand to aggravate the natural dèsagrémens of the situation. About an hour after dawn, when I turned out on deck, there was nothing visible but a warm grey mist; but a knotty old pilot on deck told me we were only going six knots an hour against tide and wind, and that we were likely to make less way as the day wore on. In fact, instead of being near Baltimore, we were much nearer Fortress Monroe. Need I repeat the horrors of this day? Stewed, boiled, baked, and grilled on board this miserable Elizabeth, I wished M. Montalembert could have experienced with me what such an impassive nature could inflict in misery on those around it. The captain was a shy, silent man, much given to short naps in my temporary berth, and the mate was so wild, he might have swam off with perfect propriety to the woods on either side of us, and taken to a tree as an aborigen or chimpanzee. Two men of most retiring habits, the negro, a black boy, and a very fat negress who officiated as cook, filled up the “balance” of the crew.

I could not write, for the vibration of the deck of the little craft gave a St. Vitus dance to pen and pencil; reading was out of the question from the heat and flies; and below stairs the fat cook banished repose by vapours from her dreadful caldrons, where, Medealike, she was boiling some death broth. Our breakfast was of the simplest and–may I add?–the least enticing; and if the dinner could have been worse it was so; though it was rendered attractive by hunger, and by the kindness of the sailors who shared it with me. The old pilot had a most wholesome hatred of the Britishers, and not having the least idea till late in the day that I belonged to the old country, favoured me with some very remarkable views respecting their general mischievousness and inutility. As soon as he found out my secret he became more reserved, and explained to me that he had some reason for not liking us, because all he had in the world, as pretty a schooner as ever floated and a fine cargo, had been taken and burnt by the English when they sailed up the Potomac to Washington. He served against us at Bladensburg. I did not ask him how fast he ran; but he had a good rejoinder ready if I had done so, inasmuch as he was up West under Commodore Perry on the lakes when we suffered our most serious reverses. Six knots an hour! hour after hour! And nothing to do but to listen to the pilot.

On both sides a line of forest just visible above the low shores. Small coasting craft, schooners, pungys, boats laden with wood creeping along in the shallow water, or plying down empty before wind and tide.

“I doubt if we’ll be able to catch up them forts afore night,” said the skipper. The pilot grunted, “I rather think yu’ll not.” “H____ and thunder! Then we’ll have to lie off till daylight?” “They may let you pass, Captain Squires, as you’ve this Europe-an on board, but anyhow we can’t fetch Baltimore till late at night or early in the morning.”

I heard the dialogue, and decided very quickly that as Annapolis lay somewhere ahead on our left, and was much nearer than Baltimore, it would be best to run for it while there was daylight. The captain demurred. He had been ordered to take his vessel to Baltimore, and General Butler might come down on him for not doing so; but I proposed to sign a letter stating he had gone to Annapolis at my request, and the steamer was put a point or two to westward, much to the pleasure of the Palinurus, whose “old woman” lived in the town. I had an affection for this weather-beaten, watery-eyed, honest old fellow, who hated us as cordially as Jack detested his Frenchman in the old days before ententes cordiales were known to the world. He was thoroughly English in his belief that he belonged to the only sailor race in the world, and that they could beat all mankind in seamanship; and he spoke in the most unaffected way of the Britishers as a survivor of the old war might do of Johnny Crapaud–”They were brave enough no doubt, but, Lord bless you, see them in a gale of wind! or look at them sending down top-gallant masts, or anything sailor-like in a breeze. You’d soon see the differ. And, besides, they never can stand again us at close quarters.” By-and-by the houses of a considerable town, crowned by steeples, and a large Corinthian-looking building, came in view. “That’s the State House. That’s where George Washington–first in peace, first in war, and first in the hearts of his countrymen–laid down his victorious sword without any one asking him, and retired amid the applause of the civilized world.” This flight I am sure was the old man’s treasured relic of school-boy days, and I’m not sure he did not give it to me three times over. Annapolis looks very well from the river side. The approach is guarded by some very poor earthworks and one small fort. A dismantled sloop of war lay off a sea wall, banking up a green lawn covered with trees, in front of an old-fashioned pile of buildings, which formerly, I think, and very recently indeed, was occupied by the cadets of the United States Naval School. “There was a lot of them Seceders. Lord bless you! these young ones is all took by these States Rights’ doctrines–just as the ladies is caught by a new fashion.”

About seven o’clock the steamer hove alongside a wooden pier which was quite deserted. Only some ten or twelve sailing boats, yachts, and schooners lay at anchor in the placid waters of the port which was once the capital of Maryland, and for which the early Republicans prophesied a great future. But Baltimore has eclipsed Annapolis into utter obscurity. I walked to the only hotel in the place, and found that the train for the junction with Washington had started, and that the next train left at some impossible hour in the morning. It is an odd Rip Van Winkle sort of a place. Quaint-looking boarders came down to the tea-table and talked Secession, and when I was detected, as must ever soon be the case, owing to the hotel book, I was treated to some ill-favoured glances, as my recent letters have been denounced in the strongest way for their supposed hostility to States Rights and the Domestic Institution. The spirit of the people has, however, been broken by the Federal occupation, and by the decision with which Butler acted when he came down here with the troops to open communications with Washington after the Baltimoreans had attacked the soldiery on their way through the city from the north.

Tribulation.—”‘Indeed,’ I burst out, forgetting my resolution not to argue…”—War Diary of a Union Woman in the South.

July 15, 2021

July 15, 1861.—The quiet of midsummer reigns, but ripples of excitement break around us as the papers tell of skirmishes and attacks here and there in Virginia. “Rich Mountain” and “Carrick’s Ford” were the last. “You see,” said Mrs. D. at breakfast to-day, “my prophecy is coming true that Virginia will be the seat of war.” “Indeed,” I burst out, forgetting my resolution not to argue, “you may think yourselves lucky if this war turns out to have any seat in particular.”

So far, no one especially connected with me has gone to fight. How glad I am for his mother’s sake that Rob’s lameness will keep him at home. Mr. F., Mr. S., and Uncle Ralph are beyond the age for active service, and Edith says Mr. D. can’t go now. She is very enthusiastic about other people’s husbands being enrolled, and regrets that her Alex is not strong enough to defend his country and his rights.

Note: To protect Mrs. Miller’s job as a teacher in post-civil war New Orleans, her diary was published anonymously, edited by G. W. Cable, names were changed and initials were generally used instead of full names—and even the initials differed from the real person’s initials. (Read Dora Richards Miller’s biographical sketch.)

A Diary of American Events – July 15, 1861

July 15, 2021

–General Patterson’s division, in its advance upon Winchester, Va., had a very brilliant skirmish to-day with the rebels near Bunker Hill, about nine miles from Martinsburg. The Rhode Island battery and the Twenty-first and Twenty-third Pennsylvania Regiments headed the advancing column, supported by the Second United Cavalry, under Colonel Thomas. When near Bunker Hill the rebel cavalry, 600 strong, under Colonel Stuart, charged the United States infantry, not perceiving the battery behind them. The infantry at once opened their lines, and the Rhode Island artillery poured in a discharge of grape and shell that sent the rebel cavalry reeling back. The United States cavalry then charged and pursued them for two miles, until they were entirely routed.–(Doc. 92.)

–Brig.-Gen. Hurlbut issued a proclamation to the citizens of Northeastern Missouri, denouncing the false and designing men who are seeking to overthrow the Government. He warns them that the time for tolerating treason has passed, and that the man or body of men who venture to stand in defiance of the supreme authority of the Union, peril their lives in the attempt. He says the character of the resistance which has been made, is in strict conformity with the source from which it originated. Cowardly assassins watch for opportunities to murder, and become heroes among their associated band by slaughtering, by stealth, those whom openly they dare not meet. This system, hitherto unknown to civilized warfare, is the natural fruit which treason bears. The process of the criminal courts as administered in disaffected districts will not cure this system of assassination, but the stern and imperative demand of a military necessity, and the duty of self-protection, will furnish a sharp and decisive remedy in the justice of a court-martial–(Doc. 93.)

–A Peace Meeting was held at Nyack, Rockland Co., N. Y. Addresses were delivered, and resolutions were adopted, deprecating the present war.–(Doc. 96.)

Civil War Day-By-Day

July 15, 2021

July 15, 1861

A Chronological History of the Civil War in America1

- Union army, 40,000 strong, under McDowell, moved from encampments in and around Washington and Arlington Heights toward Fairfax

Court House, Va. - Skirmish at Bunker Hill, Va.; rebels routed.

- A Chronological History of the Civil War in America by Richard Swainson Fisher, New York, Johnson and Ward, 1863

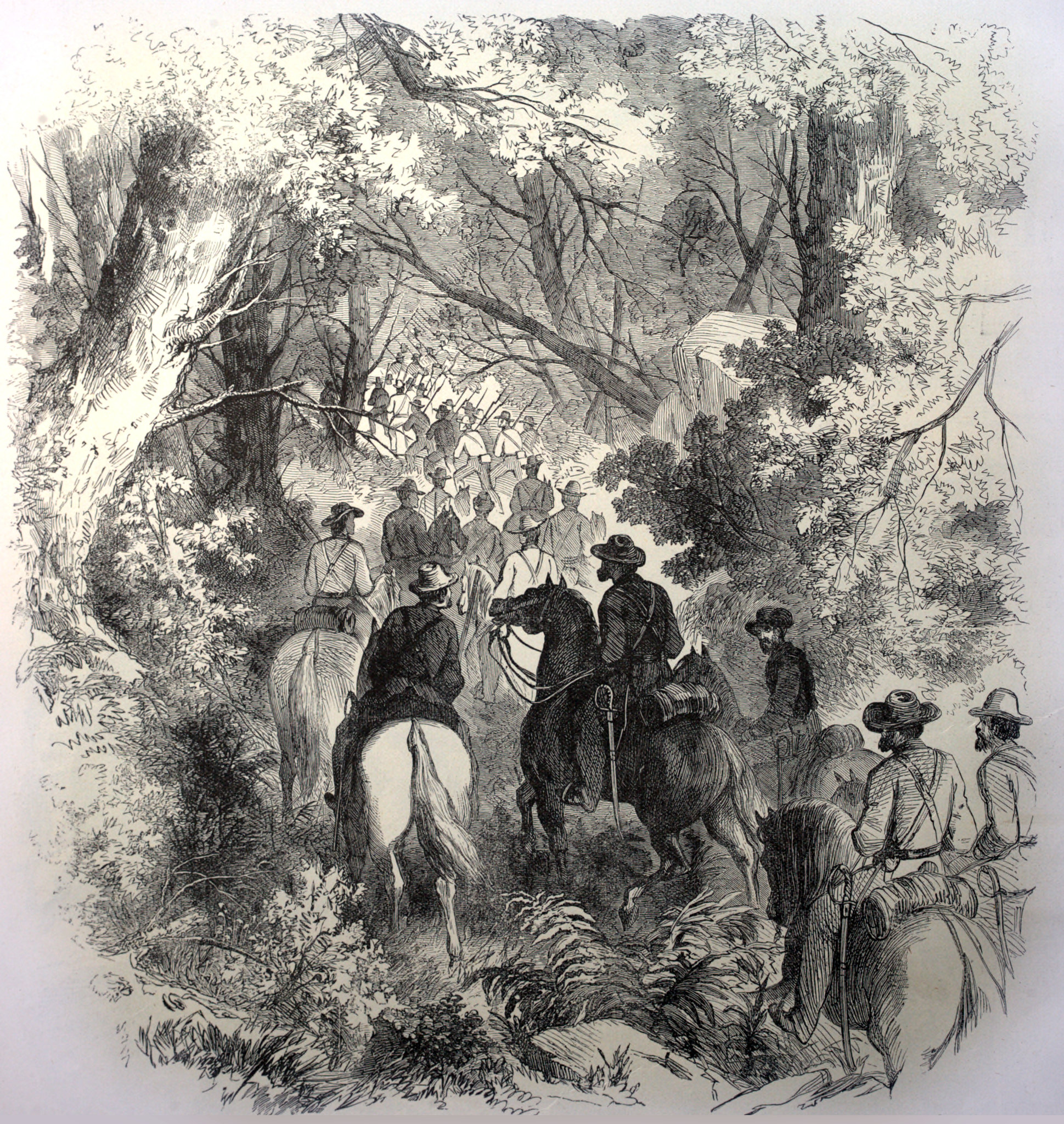

Advance of General Rosecrans’s Division

July 14, 2021

Advance of General Rosecrans’s Division through the Forests of Laurel Hill to Attack the Confederate Intrenchments at Rich Mountain, July 11, 1861

“General McClellan’s plan for attacking the Confederates under General Garnett in Western Virginia and driving them beyond the Alleghenies involved the surprise of a large body strongly intrenched at Rich Mountain, in a position commanding the turnpike over Laurel Hill. He detailed General Rosecrans to surprise them. This in turn involved a circuitous march through the dense forests of Laurel Hill, over a wild and broken country. General Rosecrans’s column of 1,600 men was guided by a woodsman named David L. Hart, who described the march as follows: ‘We started at daylight, and I led, accompanied by Colonel Lander, through a pathless wood, obstructed by bushes, laurels, fallen timber and rocks, followed by the whole division in perfect silence. Our circuit was about five miles; rain fell, the bushes wet us through, and it was very cold. At noon we came upon the Confederate pickets, and after drawing the dampened charges from our guns immediately opened action.’ The result of the battle is well known. It ended in the utter rout and final capture of the Confederates under Colonel Pegram, with a loss of 150 killed and 300 wounded.”

(from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War…, edited by Louis Shepheard Moat, Published by Mrs. Frank Leslie, New York, 1895)

“Something will be done soon.”—Horatio Nelson Taft

July 14, 2021

SUNDAY 14

This has been a cool day, almost too cold for comfort. Troops have been going over the River today and others leave early tomorrow morning. Something will be done soon. I went out to church with wife, heard Chaplin of the 2nd N H Reg’t. His Regt leave[s] in the morning for Virginia. Went down to Willards with Lieut. Swan. Saw Mr Pomeroy (MC) and other gentlemen, heard no particular news, quite a crowd there. House full of Military and (MCs).

______

The three diary manuscript volumes, Washington during the Civil War: The Diary of Horatio Nelson Taft, 1861-1865, are available online at The Library of Congress.

Mary Chesnut’s Diary.—”I did not care a fig for a description of the war council.”

July 14, 2021

July 14th.–Mr. Chesnut remained closeted with the President and General Lee all the afternoon. The news does not seem pleasant. At least, he is not inclined to tell me any of it. He satisfied himself with telling me how sensible and soldierly this handsome General Lee is. General Lee’s military sagacity was also his theme. Of course the President dominated the party, as well by his weight of brain as by his position. I did not care a fig for a description of the war council. I wanted to know what is in the wind now?

Rebel War Clerk

July 14, 2021

JULY 14th.—The Secretary is sick again. He has been recommended by his physician to spend some days in the country; and to-morrow he will leave with his family. What will be the consequence?

Extracts from the journal of Commander Semmes, C.S. Navy, commanding C.S.S. Sumter

July 14, 2021

William Howard Russell’s Diary: Fortress Monroe.—General Butler.—Hospital accommodation.—Wounded soldiers.—Aristocratic pedigrees.—A great gun.—Newport News.—Fraudulent contractors.—Artillery practice.—Contraband negroes.—Confederate lines.—Tombs of American loyalists.—Troops and contractors.—Duryea’s New York Zouaves.—Military calculations.

July 14, 2021

July 14th.–At six o’clock this morning the steamer arrived at the wharf under the walls of Fortress Monroe, which presented a very different appearance from the quiet of its aspect when first I saw it, some months ago. Camps spread around it, the parapets lined with sentries, guns looking out towards the land, lighters and steamers alongside the wharf, a strong guard at the end of the pier, passes to be scrutinised and permits to be given. I landed with the members of the Sanitary Commission, and repaired to a very large pile of buildings, called “The Hygeia Hotel,” for once on a time Fortress Monroe was looked upon as the resort of the sickly, who required bracing air and an abundance of oysters; it is now occupied by the wounded in the several actions and skirmishes which have taken place, particularly at Bethel; and it is so densely crowded that we had difficulty in procuring the use of some small dirty rooms to dress in. As the business of the Commission was principally directed to ascertain the state of the hospitals, they considered it necessary in the first instance to visit General Butler, the commander of the post, who has been recommending himself to the Federal Government by his activity ever since he came down to Baltimore, and the whole body marched to the fort, crossing the drawbridge after some parley with the guard, and received permission, on the production of passes, to enter the court.

The interior of the work covers a space of about seven or eight acres, as far as I could judge, and is laid out with some degree of taste; rows of fine trees border the walks through the grass plots; the officers’ quarters, neat and snug, are surrounded with little patches of flowers, and covered with creepers. All order and neatness, however, were fast disappearing beneath the tramp of mailed feet, for at least 1200 men had pitched their tents inside the place. We sent in our names to the General, who lives in a detached house close to the sea face of the fort, and sat down on a bench under the shade of some trees, to avoid the excessive heat of the sun until the commander of the place could receive the Commissioners. He was evidently in no great hurry to do so. In about half an hour an aide-de-camp came out to say that the General was getting up, and that he would see us after breakfast. Some of the Commissioners, from purely sanitary considerations, would have been much better pleased to have seen him at breakfast, as they had only partaken of a very light meal on board the steamer at five o’clock in the morning; but we were interested meantime by the morning parade of a portion of the garrison, consisting of 300 regulars, a Massachusetts’ volunteer battalion, and the 2nd NewYork Regiment.

It was quite refreshing to the eye to see the cleanliness of the regulars–their white gloves and belts, and polished buttons, contrasted with the slovenly aspect of the volunteers; but, as far as the material went, the volunteers had by far the best of the comparison. The civilians who were with me did not pay much attention to the regulars, and evidently preferred the volunteers, although they could not be insensible to the magnificent drum-major who led the band of the regulars. Presently General Butler came out of his quarters, and walked down the lines, followed by a few officers. He is a stout, middle-aged man, strongly built, with coarse limbs, his features indicative of great shrewdness and craft, his forehead high, the elevation being in some degree due perhaps to the want of hair; with a strong obliquity of vision, which may perhaps have been caused by an injury, as the eyelid hangs with a peculiar droop over the organ.

The General, whose manner is quick, decided, and abrupt, but not at all rude or unpleasant, at once acceded to the wishes of the Sanitary Commissioners, and expressed his desire to make my stay at the fort as agreeable and useful as he could. “You can first visit the hospitals in company with these gentlemen, and then come over with me to our camp, where I will show you everything that is to be seen. I have ordered a steamer to be in readiness to take you to Newport News.” He speaks rapidly, and either affects or possesses great decision. The Commissioners accordingly proceeded to make the most of their time in visiting the Hygeia Hotel, being accompanied by the medical officers of the garrison.

The rooms, but a short time ago occupied by the fair ladies of Virginia, when they came down to enjoy the sea breezes, were now crowded with Federal soldiers, many of them suffering from the loss of limb or serious wounds, others from the worst form of camp disease. I enjoyed a small national triumph over Dr. Bellows, the chief of the Commissioners, who is of the “sangre azul” of Yankeeism, by which I mean that he is a believer, not in the perfectibility, but in the absolute perfection, of New England nature, which is the only human nature that is not utterly lost and abandoned–Old England nature, perhaps, being the worst of all. We had been speaking to the wounded men in several rooms, and found most of them either in the listless condition consequent upon exhaustion, or with that anxious air which is often observable on the faces of the wounded when strangers approach. At last we came into a room in which two soldiers were sitting up, the first we had seen, reading the newspapers. Dr. Bellows asked where they came from; one was from Concord, the other from Newhaven. “You see, Mr. Russell,” said Dr. Bellows, “how our Yankee soldiers spend their time. I knew at once they were Americans when I saw them reading newspapers.” One of them had his hand shattered by a bullet, the other was suffering from a gun-shot wound through the body. “Where were you hit?” I inquired of the first. “Well,” he said, “I guess my rifle went off when I was cleaning it in camp.” “Were you wounded at Bethel?” I asked of the second. “No, sir,” he replied; “I got this wound from a comrade, who discharged his piece by accident in one of the tents as I was standing outside.” “So,” said I, to Dr. Bellows, “whilst the Britishers and Germans are engaged with the enemy, you Americans employ your time shooting each other!”

These men were true mercenaries, for they were fighting for money–I mean the strangers. One poor fellow from Devonshire said, as he pointed to his stump, “I wish I had lost it for the sake of the old island, sir,” paraphrasing Sarsfield’s exclamation as he lay dying on the field. The Americans were fighting for the combined excellences and strength of the States of New England, and of the rest of the Federal power over the Confederates, for they could not in their heart of hearts believe the Old Union could be restored by force of arms. Lovers may quarrel and may reunite, but if a blow is struck there is no redintegratio amoris possible again. The newspapers and illustrated periodicals which they read were the pabulum that fed the flames of patriotism incessantly. Such capacity for enormous lying, both in creation and absorption, the world never heard. Sufficient for the hour is the falsehood.

There were lady nurses in attendance on the patients; who followed–let us believe, as I do, out of some higher motive than the mere desire of human praise–the example of Miss Nightingale. I loitered behind in the rooms, asking many questions respecting the nationality of the men, in which the members of the Sanitary Commission took no interest, and I was just turning into one near the corner of the passage when I was stopped by a loud smack. A young Scotchman was dividing his attention between a basin of soup and a demure young lady from Philadelphia, who was feeding him with a spoon, his only arm being engaged in holding her round the waist, in order to prevent her being tired, I presume. Miss Rachel, or Deborah, had a pair of very pretty blue eyes, but they flashed very angrily from under her trim little cap at the unwitting intruder, and then she said, in severest tones, “Will you take your medicine, or not?” Sandy smiled, and pretended to be very penitent.

When we returned with the doctors from our inspection we walked round the parapets of the fortress, why so called I know not, because it is merely a fort. The guns and mortars are old-fashioned and heavy, with the exception of some new-fashioned and very heavy Columbiads, which are cast-iron 8-, 10-, and 12-inch guns, in which I have no faith whatever. The armament is not sufficiently powerful to prevent its interior being searched out by the long range fire of ships with rifle guns, or mortar boats; but it would require closer and harder work to breach the masses of brick and masonry which constitute the parapets and casemates. The guns, carriages, rammers, shot, were dirty, rusty, and neglected; but General Butler told me he was busy polishing up things about the fortress as fast as he could.

Whilst we were parading these hot walls in the sunshine, my companions were discussing the question of ancestry. It appears your New Englander is very proud of his English descent from good blood, and it is one of their isms in the Yankee States that they are the salt of the British people and the true aristocracy of blood and family, whereas we in the isles retain but a paltry share of the blue blood denied by incessant infiltrations of the muddy fluid of the outer world. This may be new to us Britishers, but is a Q. E. D. If a gentleman left Europe 200 years ago, and settled with his kin and kith, intermarrying his children with their equals, and thus perpetuating an ancient family, it is evident he may be regarded as the founder of a much more honourable dynasty than the relative who remained behind him, and lost the old family place, and sunk into obscurity. A singular illustration of the tendency to make much of themselves may be found in the fact, that New England swarms with genealogical societies and bodies of antiquaries, who delight in reading papers about each other’s ancestors, and tracing their descent from Norman or Saxon barons and earls. The Virginians opposite, who are flouting us with their Confederate flag from Sewall’s Point, are equally given to the “genus et proavos.”

At the end of our promenade round the ramparts, Lieutenant Butler, the General’s nephew and aide-decamp, came to tell us the boat was ready, and we met His Excellency in the court-yard, whence we walked down to the wharf. On our way, General Butler called my attention to an enormous heap of hollow iron lying on the sand, which was the Union gun that is intended to throw a shot of some 350 lbs. weight or more, to astonish the Confederates at Sewall’s Point opposite, when it is mounted. This gun, if I mistake not, was made after the designs of Captain Rodman, of the United States artillery, who in a series of remarkable papers, the publication of which has cost the country a large sum of money, has given us the results of long continued investigations and experiments on the best method of cooling masses of iron for ordnance purposes, and of making powder for heavy shot. The piece must weigh about 20 tons, but a similar gun, mounted on an artificial island called the Rip Raps, in the Channel opposite the fortress, is said to be worked with facility. The Confederates have raised some of the vessels sunk by the United States officers when the Navy Yard at Gosport was destroyed, and as some of these are to be converted into rams, the Federals are preparing their heaviest ordnance, to try the effect of crushing weights at low velocities against their sides, should they attempt to play any pranks among the transport vessels. The General said: “It is not by these great masses of iron this contest is to be decided: we must bring sharp points of steel, directed by superior intelligence.” Hitherto General Butler’s attempts at Big Bethel have not been crowned with success in employing such means, but it must be admitted that, according to his own statement, his lieutenants were guilty of carelessness and neglect of ordinary military precautions in the conduct of the expedition he ordered. The march of different columns of troops by night concentrating on a given point is always liable to serious interruptions, and frequently gives rise to hostile encounters between friends, in more disciplined armies than the raw levies of United States volunteers.

When the General, Commissioners, and Staff had embarked, the steamer moved across the broad estuary to Newport News. Among our passengers were several medical officers in attendance on the Sanitary Commissioners, some belonging to the army, others who had volunteered from civil life. Their discussion of professional questions and of relative rank assumed such a personal character, that General Butler had to interfere to quiet the disputants, but the exertion of his authority was not altogether successful, and one of the angry gentlemen said in my hearing, “I’m d–d if I submit to such treatment if all the lawyers in Massachusetts with stars on their collars were to order me to-morrow.”

On arriving at the low shore of Newport News we landed at a wooden jetty, and proceeded to visit the camp of the Federals, which was surrounded by a strong entrenchment, mounted with guns on the water face; and on the angles inland, a broad tract of cultivated country, bounded by a belt of trees, extended from the river away from the encampment; but the Confederates are so close at hand that frequent skirmishes have occurred between the foraging parties of the garrison and the enemy, who have on more than one occasion pursued the Federals to the very verge of the woods.

Whilst the Sanitary Commissioners were groaning over the heaps of filth which abound in all camps where discipline is not most strictly observed, I walked round amongst the tents, which, taken altogether, were in good order. The day was excessively hot, and many of the soldiers were laying down in the shade of arbours formed of branches from the neighbouring pine wood, but most of them got up when they heard the General was coming round. A sentry walked up and down at the end of the street, and as the General came up to him he called out “Halt.” The man stood still. “I just want to show you, sir, what scoundrels our Government has to deal with. This man belongs to a regiment which has had new clothing recently served out to it. Look what it is made of.” So saying the General stuck his fore-finger into the breast of the man’s coat, and with a rapid scratch of his nail tore open the cloth as if it was of blotting paper. “Shoddy sir. Nothing but shoddy. I wish I had these contractors in the trenches here, and if hard work would not make honest men of them, they’d have enough of it to be examples for the rest of their fellows.”

A vivacious prying man, this Butler, full of bustling life, self-esteem, revelling in the exercise of power. In the course of our rounds we were joined by Colonel Phelps, who was formerly in the United States army, and saw service in Mexico, but retired because he did not approve of the manner in which promotions were made, and who only took command of a Massachusetts regiment because he believed he might be instrumental in striking a shrewd blow or two in this great battle of Armageddon–a tall, saturnine, gloomy, angry-eyed, sallow man, soldier-like too, and one who places old John Brown on a level with the great martyrs of the Christian world. Indeed one, not so fierce as he, is blasphemous enough to place images of our Saviour and the hero of Harper’s Ferry on the mantelpiece, as the two greatest beings the world has ever seen. “Yes, I know them well. I’ve seen them in the field. I’ve sat with them at meals. I’ve travelled through their country. These Southern slave-holders are a false, licentious, godless people. Either we who obey the laws and fear God, or they who know no God except their own will and pleasure, and know no law except their passions, must rule on this continent, and I believe that Heaven will help its own in the conflict they have provoked. I grant you they are brave enough, and desperate too, but surely justice, truth, and religion, will strengthen a man’s arm to strike down those who have only brute force and a bad cause to support them.” But Colonel Phelps was not quite indifferent to material aid, and he made a pressing appeal to General Butler to send him some more guns and harness for the field-pieces he had in position, because, said he, “in case of attack, please God I’ll follow them up sharp, and cover these fields with their bones.” The General had a difficulty about the harness, which made Colonel Phelps very grim, but General Butler had reason in saying he could not make harness, and so the Colonel must be content with the results of a good rattling fire of round, shell, grape, and cannister, if the Confederates are foolish enough to attack his batteries. There was nothing to complain of in the camp, except the swarms of flies, the very bad smells, and perhaps the shabby clothing of the men. The tents were good enough. The rations were ample, but nevertheless there was a want of order, discipline, and quiet in the lines which did not augur well for the internal economy of the regiments. When we returned to the river face, General Butler ordered some practice to be made with a Sawyer rifle gun, which appeared to be an ordinary cast-iron piece, bored with grooves, on the shunt principle, the shot being covered with a composition of a metallic amalgam like zinc and tin, and provided with flanges of the same material to fit the grooves. The practice was irregular and unsatisfactory. At an elevation of 24 degrees, the first shot struck the water at a point about 2000 yards distant. The piece was then further elevated, and the shot struck quite out of land, close to the opposite bank, at a distance of nearly three miles. The third shot rushed with a peculiar hurtling noise out of the piece, and flew up in the air, falling with a splash into the water about 1500 yards away. The next shot may have gone half across the continent, for assuredly it never struck the water, and most probably ploughed its way into the soft ground at the other side of the river. The shell practice was still worse, and on the whole I wish our enemies may always fight us with Sawyer guns, particularly as the shells cost between £6 and £7 a-piece.

From the fort the General proceeded to the house of one of the officers, near the jetty, formerly the residence of a Virginian farmer, who has now gone to Secessia, where we were most hospitably treated at an excellent lunch, served by the slaves of the former proprietor. Although we boast with some reason of the easy level of our mess-rooms, the Americans certainly excel us in the art of annihilating all military distinctions on such occasions as these; and I am not sure the General would not have liked to place a young Doctor in close arrest, who suddenly made a dash at the liver wing of a fowl on which the General was bent with eye and fork, and carried it off to his plate. But on the whole there was a good deal of friendly feeling amongst all ranks of the volunteers, the regulars being a little stiff and adherent to etiquette.

In the afternoon the boat returned to Fortress Monroe, and the general invited me to dinner, where I had the pleasure of meeting Mrs. Butler, his staff, and a couple of regimental officers from the neighbouring camp. As it was still early, General Butler proposed a ride to visit the interesting village of Hampton, which lies some six or seven miles outside the fort, and forms his advance post. A powerful charger, with a tremendous Mexican saddle, fine housings, blue and gold embroidered saddle-cloth, was brought to the door for your humble servant, and the General mounted another, which did equal credit to his taste in horseflesh; but I own I felt rather uneasy on seeing that he wore a pair of large brass spurs, strapped over white jean brodequins. He took with him his aide-de-camp and a couple of orderlies. In the precincts of the fort outside, a population of contraband negroes has been collected, whom the General employs in various works about the place, military and civil; but I failed to ascertain that the original scheme of a debit and credit account between the value of their labour and the cost of their maintenance had been successfully carried out. The General was proud of them, and they seemed proud of themselves, saluting him with a ludicrous mixture of awe and familiarity as he rode past. “How do, Massa Butler? How do, General?” accompanied by absurd bows and scrapes. “Just to think,” said the General, “that every one of these fellows represents some 1000 dollars at least out of the pockets of the chivalry yonder.” “Nasty, idle, dirty beasts,” says one of the staff, sotto voce; “I wish to Heaven they were all at the bottom of the Chesapeake. The General insists on it that they do work, but they are far more trouble than they are worth.”

The road towards Hampton traverses a sandy spit, which, however, is more fertile than would be supposed from the soil under the horses’ hoofs, though it is not in the least degree interesting. A broad creek or river interposed between us and the town, the bridge over which had been destroyed. Workmen were busy repairing it, but all the planks had not yet been laid down or nailed, and in some places the open space between the upright rafters allowed us to see the dark waters flowing beneath. The Aide said, “I don’t think, General, it is safe to cross;” but his chief did not mind him until his horse very nearly crashed through a plank, and only regained its footing with unbroken legs by marvellous dexterity; whereupon we dismounted, and, leaving the horses to be carried over in the ferry boat, completed the rest of the transit, not without difficulty. At the other end of the bridge a street lined with comfortable houses, and bordered with trees, led us into the pleasant town or village of Hampton–pleasant once, but now deserted by all the inhabitants except some pauperised whites and a colony of negroes. It was in full occupation of the Federal soldiers, and I observed that most of the men were Germans, the garrison at Newport News being principally composed of Americans. The old red brick houses, with cornices of white stone; the narrow windows and high gables; gave an aspect of antiquity and European comfort to the place, the like of which I have not yet seen in the States. Most of the shops were closed; in some the shutters were still down, and the goods remained displayed in the windows. “I have allowed no plundering,” said the General; “and if I find a fellow trying to do it, I will hang him as sure as my name is Butler. See here,” and as he spoke he walked into a large woollen-draper’s shop, where bales of cloth were still lying on the shelves, and many articles such as are found in a large general store in a country town were disposed on the floor or counters; “they shall not accuse the men under my command of being robbers.” The boast, however, was not so well justified in a visit to another house occupied by some soldiers. “Well,” said the General, with a smile, “I daresay you know enough of camps to have found out that chairs and tables are irresistible; the men will take them off to their tents, though they may have to leave them next morning.”

The principal object of our visit was the fortified trench which has been raised outside the town towards the Confederate lines. The path lay through a churchyard filled with most interesting monuments. The sacred edifice of red brick, with a square clock tower rent by lightning, is rendered interesting by the fact that it is almost the first church built by the English colonists of Virginia. On the tombstones are recorded the names of many subjects of his Majesty George III., and familiar names of persons born in the early part of last century in English villages, who passed to their rest before the great rebellion of the Colonies had disturbed their notions of loyalty and respect to the Crown. Many a British subject, too, lies there, whose latter days must have been troubled by the strange scenes of the war of independence. With what doubt and distrust must that one at whose tomb I stand have heard that George Washington was making head against the troops of His Majesty King George III.! How the hearts of the old men who had passed the best years of their existence, as these stones tell us, fighting for His Majesty against the French, must have beaten when once more they heard the roar of the Frenchman’s ordnance uniting with the voices of the rebellious guns of the colonists from the plains of Yorktown against the entrenchments in which Cornwallis and his deserted band stood at hopeless bay! But could these old eyes open again, and see General Butler standing on the eastern rampart which bounds their resting-place, and pointing to the spot whence the rebel cavalry of Virginia issue night and day to charge the loyal pickets of His Majesty The Union, they might take some comfort in the fulfilment of the vaticinations which no doubt they uttered, “It cannot, and it will not, come to good.”

Having inspected the works–as far as I could judge, too extended, and badly traced – which I say with all deference to the able young engineer who accompanied us to point out the various objects of interest–the General returned to the bridge, where we remounted, and made a tour of the camps of the force intended to defend Hampton, falling back on Fortress Monroe in case of necessity. Whilst he was riding ventre d terre, which seems to be his favourite pace, his horse stumbled in the dusty road, and in his effort to keep his seat the General broke his stirrup leather, and the ponderous brass stirrup fell to the ground; but, albeit a lawyer, he neither lost his seat nor his sang froid, and calling out to his orderly “to pick up his toe plate,” the jean slippers were closely pressed, spurs and all, to the sides of his steed, and away we went once more through dust and heat so great I was by no means sorry when he pulled up outside a pretty villa, standing in a garden, which was occupied by Colonel Max Webber, of the German Turner Regiment, once the property of General Tyler. The camp of the Turners, who are members of various gymnastic societies, was situated close at hand; but I had no opportunity of seeing them at work, as the Colonel insisted on our partaking of the hospitalities of his little mess, and produced some bottles of sparkling hock and a block of ice, by no means unwelcome after our fatiguing ride. His Major, whose name I have unfortunately forgotten, and who spoke English better than his chief, had served in some capacity or other in the Crimea, and made many inquiries after the officers of the Guards whom he had known there. I took an opportunity of asking him in what state the troops were. “The whole thing is a robbery,” he exclaimed; “this war is for the contractors; the men do not get a third of what the Government pay for them; as for discipline, my God! it exists not. We Germans are well enough, of course; we know our affair; but as for the Americans, what would you? They make colonels out of doctors and lawyers, and captains out of fellows who are not fit to brush a soldier’s shoe.” “But the men get their pay?” “Yes; that is so. At the end of two months, they get it, and by that time it is due to sutlers, who charge them 100 per cent.”

It is easy to believe these old soldiers do not put much confidence in General Butler, though they admit his energy. “Look you; one good officer with 5000 steady troops, such as we have in Europe, shall come down any night and walk over us all into Fortress Monroe whenever he pleased, if he knew how these troops were placed.”

On leaving the German Turners, the General visited the camp of Duryea’s New York Zouaves, who were turned out at evening parade, or more properly speaking, drill. But for the ridiculous effect of their costume the regiment would have looked well enough; but riding down on the rear of the ranks the discoloured napkins tied round their heads, without any fez cap beneath, so that the hair sometimes stuck up through the folds, the ill-made jackets, the loose bags of red calico hanging from their loins, the long gaiters of white cotton–instead of the real Zouave yellow and black greave, and smart white gaiter–made them appear such military scarecrows, I could scarcely refrain from laughing outright. Nevertheless the men were respectably drilled, marched steadily in columns of company, wheeled into line, and went past at quarter distance at the double much better than could be expected from the short time they had been in the field, and I could with all sincerity say to Col. Duryea, a smart and not unpretentious gentleman, who asked my opinion so pointedly that I could not refuse to give it, that I considered the appearance of the regiment very creditable. The shades of evening were now falling, and as I had been up before 5 o’clock in the morning, I was not sorry when General Butler said, “Now we will go home to tea, or you will detain the steamer.” He had arranged before I started that the vessel, which in ordinary course would have returned to Baltimore at 8 o’clock, should remain till he sent down word to the captain to go.

We scampered back to the fort, and judging from the challenges and vigilance of the sentries, and inlying pickets, I am not quite so satisfied as the Major that the enemy could have surprised the place. At the tea-table there were no additions to the General’s family; he therefore spoke without any reserve. Going over the map, he explained his views in reference to future operations, and showed cause, with more military acumen than I could have expected from a gentleman of the long robe, why he believed Fortress Monroe was the true base of operations against Richmond.

I have been convinced for some time, that if a sufficient force could be left to cover Washington, the Federals should move against Richmond from the Peninsula, where they could form their depots at leisure, and advance, protected by their gunboats, on a very short line which offers far greater facilities and advantages than the inland route from Alexandria to Richmond, which, difficult in itself from the nature of the country, is exposed to the action of a hostile population, and, above all, to the danger of constant attacks by the enemies’ cavalry, tending’ more or less to destroy all communication with the base of the Federal operations.

The threat of seizing Washington led to a concentration of the Union troops in front of it, which caused in turn the collection of the Confederates on the lines below to defend Richmond. It is plain that if the Federals can cover Washington, and at the same time assemble a force at Monroe strong enough to march on Richmond, as they desire, the Confederates will be placed in an exceedingly hazardous position, scarcely possible to escape from; and there is no reason why the North, with their overwhelming preponderance, should not do so, unless they be carried away by the fatal spirit of brag and bluster which comes from their press to overrate their own strength and to despise their enemy’s. The occupation of Suffolk will be seen, by any one who studies the map, to afford a most powerful leverage to the Federal forces from Monroe in their attempts to turn the enemy out of their camps of communication, and to enable them to menace Richmond as well as the Southern States most seriously.

But whilst the General and I are engaged over our maps and mint juleps, time flies, and at last I perceive by the clock that it is time to go. An aide is sent to stop the boat, but he returns ere I leave with the news that “She is gone.” Whereupon the General sends for the Quartermaster Talmadge, who is out in the camps, and only arrives in time to receive a severe “wigging.” It so happened that I had important papers to send off by the next mail from New York, and the only chance of being able to do so depended on my being in Baltimore next day. General Butler acted with kindness and promptitude in the matter. “I promised you should go by the steamer, but the captain has gone off without orders or leave, for which he shall answer when I see him. Meantime it is my business to keep my promise. Captain Talmadge, you will at once go down and give orders to the most suitable transport steamer or chartered vessel available, to get up steam at once and come up to the wharf for Mr. Russell.”

Whilst I was sitting in the parlour which served as the General’s office, there came in a pale, brighteyed, slim young man in a subaltern’s uniform, who sought a private audience, and unfolded a plan he had formed, on certain data gained by nocturnal expeditions, to surprise a body of the enemy’s cavalry which was in the habit of coming down every night and disturbing the pickets at Hampton. His manner was so eager, his information so precise, that the General could not refuse his sanction, but he gave it in a characteristic manner. “Well, sir, I understand your proposition. You intend to go out as a volunteer to effect this service. You ask my permission to get men for it. I cannot grant you an order to any of the officers in command of regiments to provide you with these; but if the Colonel of your regiment wishes to give leave to his men to volunteer, and they like to go with you, I give you leave to take them. I wash my hands of all responsibility in the affair.” The officer bowed and retired, saying, “That is quite enough, General.”1

At 10 o’clock the Quartermaster came back to say that a screw steamer called the Elizabeth was getting up steam for my reception, and I bade good-by to the General, and walked down with his aide and nephew, Lieutenant Butler, to the Hygeia Hotel to get my light knapsack. It was a lovely moonlight night, and as I was passing down an avenue of trees an officer stopped me, and exclaimed, “General Butler, I hear you have given leave to Lieutenant Blank to take a party of my regiment and go off scouting to-night after the enemy. It is too hard that–” What more he was going to say I know not, for I corrected the mistake, and the officer walked hastily on towards the General’s quarters. On reaching the Hygeia Hotel I was met by the correspondent of a New York paper, who as commissary-general, or, as they are styled in the States, officer of subsistence, had been charged to get the boat ready, and who explained to me it would be at least an hour before the steam was up; and whilst I was waiting in the porch I heard many Virginian, and old world stories as well, the general upshot of which was that all the rest of the world could he “done” at cards, in love, in drink, in horseflesh, and in fighting, by the true-born American. Gen. Butler came down after a time, and joined our little society, nor was he by any means the least shrewd and humorous raconteur of the party. At 11 o’clock the Elizabeth uttered some piercing cries, which indicated she had her steam up; and so I walked down to the jetty, accompanied by my host and his friends, and wishing them good bye, stepped on board the little vessel, and with the aid of the negro cook, steward, butler, boots, and servant, roused out the captain from a small wooden trench which he claimed as his berth, turned into it, and fell asleep just as the first difficult convulsions of the screw aroused the steamer from her coma, and forced her languidly against the tide in the direction of Baltimore.

__________

1 It may be stated here, that this expedition met with a disastrous result. If I mistake not, the officer, and with him the correspondent of a paper who accompanied him, were killed by the cavalry whom he meant to surprise, and several of the volunteers were also killed or wounded.

“The latest reliable news is that we are neither in the United States or State service, nor ever have been..,”–Army letters of Oliver Willcox Norton.

July 14, 2021

Camp Wright, Hulton, Penm.,

July 14, 1861.

Dear Sister L.:–

I spent the morning of the Fourth in writing letters. In the afternoon Colonel Grant read the Declaration of Independence, and Captain Porter delivered an oration to the soldiers and citizens in a neighboring grove, after which we had a review of the four regiments and a dress parade and adjourned.

Since the Fourth, there has been considerable excitement in reference to our pay. Orders to pay and countermands have been received in quick succession. Seven different days have been set, on which we were to receive our $17.23, which, probably is all we will ever get. Payment is now postponed to Tuesday. Our time, as made out on the pay-roll, closes one week from to-day (the 21st), but I doubt our getting home before the 1st of August.

The latest reliable news is that we are neither in the United States or State service, nor ever have been, and that we will all have to be mustered in for three months before we can draw a cent of pay. This will be done to-morrow.

The Erie Regiment is one grand fizzle out. We left home full of fight, earnestly desiring a chance to mingle with the hosts that fight under the Stars and Stripes. For two months we drilled steadily, patiently waiting the expected orders which never came but to be countermanded. We have now come to the conclusion that we will have no chance, and we are waiting in sullen silence and impatience for the expiration of our time. The State of Pennsylvania cannot furnish a better regiment than ours, and yet, where is it?

I try to look beyond this abuse and see a glorious government that must be sustained, and I feel as ready to enlist for the war to-day as I did on the 26th of April. I have written H. B. to find out what inducements there are to join his company. I would like to go back to old Ararat again and go in with him and D. T. I think if they raise any company there at all, it will be a sterling good one.

I am glad you write so much news when you write. Father’s letters are just like newspaper articles. If any letters come there, for me, please send them with the least possible delay.