(April to the middle of July)

Arrangements were made to quarter the regiment in the various sail lofts and store-houses. Double bunks, three tiers high, built to hold two men each, filled the room, with numerous narrow passages running between them. My company was assigned the upper floor of the first store room to the left, on entering. Company A and the band having the ground floor. In one corner of our room was a little partition, separating the company officers. The place was commodious enough, and kept scrupulously clean. I was given an upper front berth, in company with a young fellow from New Jersey named Dodd, and together we passed three months as bedfellows on the best of terms. He was bright, intelligent, and proved a pleasant companion.

This yard is a most delightful spot, particularly at this season of the year. It is entirely enclosed with a high brick wall, having a fine entrance, ornamented with anchors, cannons, and other naval devices. A beautiful, well shaded avenue runs from the entrance to the water, flanked by pretty grass plots; at many of the angles are picturesque arrangements of cannon balls, curious old cannons, etc. Around the top wall are perched little sentry boxes within sight of each other and hailing distance; in them our regiment performs most of its duty, and of a fine moonlight night, the sentries pacing up and down the walls, peering into the dark shadows of the outside world, seemed very romantic. Every time the clock strikes after dark, the sentinels call off the hours, adding in a singing voice, “and all’s well!” These calls are repeated throughout the entire circuit of the wall; if there is any interruption, the sergeant of the guard is soon on hand to know the reason why. On Friday, May 3d, in the afternoon, we were paraded for review by General McDowell, Inspector General, U. S. A., and after the drill, were mustered into the United States service in our company quarters; having now become United States troops, we settled down to regular garrison routine, drilling assiduously, two hours every morning and every afternoon, occasionally firing at targets with ball cartridges. This part of the duty we liked, and averaged very fair shooting, although we were obliged to fire with bayonets fixed, which made the musket too heavy for me to hold steady enough for good shooting. Every evening at five o’clock, we fell in for dress parade on the main avenue, which became the fashion for the aristocrats of the city, and scores of fine ladies drove to the yard every evening, to see the parade and listen to the superb music of Dodworth’s band. The regiment, after it received its uniforms, made a fine appearance, drilled with great precision, and had the reputation of being a swell affair; this gave it great importance in the eyes of society people. It is in fact, a regiment mostly of very fine looking young fellows.

Our food is cooked by men employed for that purpose, so we have none but strictly military duties to perform; of course we wash our own clothes, and at first found it rather hard work to get our flannel shirts clean in cold water, but outside of this, and keeping our own quarters well swept, we do no police duty, that being done by marines on duty in the yard. By degrees we became initiated into the mysteries of a soldier’s life. Reveille sounds at daybreak, when all hands turn out, dress themselves, and fall in for roll call; this over, we put our quarters in order, then go to the hydrants in the street and perform our morning ablutions, stripped to the waist, dousing ourselves liberally with cold water, subsequently adjusting, with nice accuracy, our fresh paper collars. At seven A. M. we fall in for breakfast in one rank, march to the kitchen, and through a window receive a cup of coffee, and large slice of bread; we have the same for tea, but dinner is varied – salt pork, fresh beef, corned beef in daily rotation, with abundance of bean soup – constitutes this meal. We sit around on the curbstones to eat, and generally a great many fashionable people remain after the parade to see us dispose of our evening meal.

There is plenty of sport, fencing, leaping, running, and forever playing tricks on each other. In the evening we lie in our bunks (having no chairs or benches) and read or write, a candle stuck in the socket of a bayonet, jammed in the side of the bunk, furnishing the necessary light. Tattoo at half past eight, and taps at nine, when every light must go out, without exception. If there are any delinquents, a shower of boots, shoes, or other handy material, whizzes around their candle in the twinkling of an eye, accompanied with loud and continuous yells of “douse the glint.” The great diversion, however, is the correspondence. Everybody at home wants to hear from us, and we like to receive letters, so there is an immense amount of letter writing. Good-natured congressmen frank them for us, so it costs nothing except for stationery. This is generally highly ornamented with warlike and patriotic pictures in various colors, really very curious and interesting. One of our men, a former employee of the Post Office Department, is detailed as postmaster, and his duty is anything but a sinecure. Very free criticism of affairs military is one of our prerogatives, and the people at home get many weighty opinions on the conduct of the war; as for our ability to furnish any real information, truth obliges me to say we have to seek all our news at present from the New York papers. One of the pleasant incidents of this rather monotonous life, is the occasional detail of men to serve on board the “Anaconda,” a small war steamer that patrols the Potomac; the detail usually amounts to about a dozen men and extraordinary efforts are made to be one of the party. The boat frequently wakes up the rebel batteries about Acquia creek, and along the Virginia shore, but is principally occupied in preventing smuggling across the river. The boys come back enthusiastic over their adventures afloat, and anxious for another detail. To show what the naval people think of us, I copy the following letter addressed to our commanding officer.

United States Ship Anaconda, June 2d, 1861.

Sir:

I have great pleasure in informing you of the excellent character and conduct of the detachment of the Seventy-First Regiment, ,C °mPany C, serving on this vessel. They have my warmest thanks for their assistance in working our guns at Acquia creek; as gentlemen, soldiers, or boatmen, they do honor to their regiment. Signed,

N. Collins,

Lieutenant, Commanding.

One afternoon the President sent word that he desired to inspect and review the regiment. The next day he came, attended by several people of distinction, and passed through every company’s quarters in the yard; we were all drawn up within our own rooms, and the President passed in front of us, shaking hands with every man. Afterwards we fell in for parade, and passed in review in full marching order. He paid us several compliments, and we cheered him lustily as he rode away. Mr. Lincoln has a strange, weird, and melancholy face, which fascinates you at first sight; he seemed overwhelmed with responsibility, and looked very tired.

On the 20th of May Colonel Vosburg died of an hemorrhage, and was buried with distinguished honors. The President, Secretary Seward, half a dozen batteries, and several regiments of infantry assisting in making a very solemn and distinguished funeral. Lieutenant Colonel Martin succeeded to the command of the regiment. He is a fine, soldierly looking man, and said to be a good officer, but is apparently not much known.

Since our arrival, Washington has become an immense fortress; the streets are crowded with men in an endless variety of uniforms, and all the public buildings are more or less, turned into temporary barracks. The capitol itself is full of men, some of them terrible looking fellows, especially, the New York Fire Zouaves in their red breeches and singular dress. They are certainly a hard looking crowd, and are commanded by young Ellsworth, of fancy drill renown. They are in the rotunda, while several other regiments, are in the wings and basement. The city is being completely surrounded by a complicated and strong system of earth works, upon which heavy details from the regiments, are at work night and day; several immense forts are already fully constructed.

On the 23d of May, our regiment, in company with several others, were put on transports and sent to occupy Alexandria, until this time left in the hands of the enemy. The rebels abandoned the place at our approach, and we took possession without opposition; shortly after we landed, Colonel Ellsworth, commanding the Fire Zouaves, observing a rebel flag flying from the Marshall House, went into the hotel, ran upstairs, and hauled it down; as he was descending, with the flag in his hand, the landlord, one J. W. Jackson, met him on the stairs, armed with a shot gun, and shot him dead, Frances E. Brownell, a private in the Fire Zouaves, close at hand, instantly leveled his rifle, and shot the traitor dead, and so the young ambitious colonel was instantly revenged, and the rebel citizens taught a wholesome lesson.

This dramatic event caused great excitement, and the utmost sorrow, as great things were expected of Ellsworth. As soon as possible the colonel’s body, wrapped in an American flag, was transferred to the Navy Yard, where it lay in the engine house, and was viewed by thousands of people; so great was the interest in the young man and the tragical event, that the President himself drove down to the yard, soon after the body was deposited there, and seemed greatly affected. Two days afterwards he caused his remains to be transferred to the White House, where they lay in state and were viewed by immense throngs of people. His funeral, like that of Vosburg, was out of all proportion to his rank, but this is the very beginning of hostilities, and colonels seem to be of much importance.

About the 1st of July the troops were brigaded on the Virginia side of the river, and formed into an army, commanded by General McDowell. On the 15th of July we received orders to cross the Potomac the following day, carrying three days’ cooked rations; we marched out, about one o’clock from the yard, very cheerfully, and crossed the long bridge into Old Virginia, singing lustily, “Away Down South in Dixie,” and went into bivouac near Annandale, a distance of eight or nine miles. Here were gathered together an immense body of men, being organized into an army. Our regiment was brigaded under Colonel Burnside, with the First and Second Rhode Island regiments, and the Second New Hampshire. We had no tents or shelter of any kind, only one blanket to cover us, and what was worse than all, no old soldiers to teach us the simple tricks of campaigning comfortably. In the Navy Yard we slept on the bare boards, but that soon became easy for us; now with no boards, and no shelter when it rains, we shall be in a pretty pickle. I once wondered, I remember, what kind of beds we should have in the army; by degrees, I am finding that out, as well as some other things.

In the evening our enthusiasm burst out anew, when we saw the countless camp fires, extending in every direction as far as the eye could reach. Here around us was a veritable army, with banners, opening to our imagination, a glimpse of the glorious pomp, and circumstance of war. Later on, the music of the bands came floating over the gentle summer breeze, while the increasing darkness brought into more distinct relief the shadowy groups of soldiers sitting around the fires, or moving between the long lines of picturesquely stacked arms. At intervals were batteries of artillery, their horses tethered amongst the guns, while in rear of all, just discernible by the white canvas coverings, were wagons enough apparently, to supply the combined armies of the world.

At nine o’clock tattoo was sounded by thousands of drums and fifes, and shortly afterwards the men were mostly asleep. A young fellow named Kline (Dodd having remained in the yard on the sick list) and I slept together, and shared each other’s fortunes; we spread my rubber and woolen blankets on the ground, covering ourselves with his blankets, and without other protection from the weather slept our first sleep in the open air, with the new army of Virginia; we lay for a long time gazing at the starry heavens before we slept, our stony pillows not fitting as well as those we had been used to, but at last we slept, and only awoke at the beating of the drums for reveille.

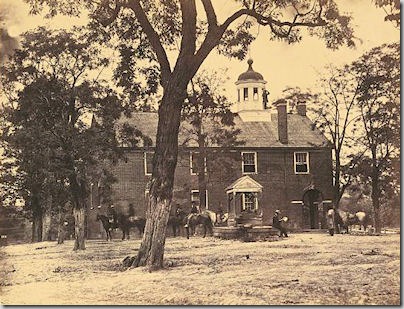

We turned out promptly, feeling pretty stiff, hair saturated with the heavy dew and generally shaky, but after a good wash at a running brook near by, and a bountiful supply of muddy coffee, were as bright and active as ever. This morning we got many particulars of the approaching campaign; it seems we are to move forward to Centreville, where the rebel army is in position; attack, and if possibly, destroy it, and so end the rebellion. We formed column, and marched soon after breakfast, with bands playing, and colors flying, in a happy frame of mind, without a thought of danger or failure. Nothing barred our progress until we approached Fairfax Court House. Here we found the roads blockaded by felled trees, and it required considerable time to remove the obstructions; shortly afterwards our advance guard exchanged shots with the enemy’s mounted videttes, and a strong line of skirmishers was thrown out, which soon cleared the way and we entered the town in great spirits, the rebels retiring as we advanced, leaving behind them a good many stores, and their flag flying from a pole in front of the court house; it was a blue cross on a red ground, with white stars on the bars. Our men quickly hauled it down and ran up the Stars and Stripes amidst vociferous cheering. The place is a wretchedly dirty, straggling little village, now almost deserted; all the men, and most of the well to do women gone, the best houses generally being deserted. Many of the women stood in the doorways watching us march past, and I am sure, I never saw so many poor, ill fed, dirty looking creatures in my life before. They are what they call poor whites here, and seem hopelessly tired out; they acted ugly, evidently considering us enemies. I fear they had cause subsequently, as many of our men acted like barbarians. We halted, stacked arms, and rested in the main street of the village. As soon as ranks were broken, the men made a dash for the large houses, plundering them right and left; what they could not carry away, in many cases, they destroyed; pianos were demolished, pictures cut from their frames, wardrobes ransacked, and most of the furniture carried out into the street. Soon the men appeared wearing tall hats, women’s bonnets, dresses, etc., loaded down with plunder which they proceeded to examine and distribute, sitting on sofas, rocking chairs, etc., in the middle of the dusty street. What was not considered portable, or worth keeping, was smashed and destroyed; in this general sack the deserted houses came in for most attention, few of those having any one in charge being molested, and I did not hear of any personal indignities. It seemed strange to me the men desired mementoes of something we did not have to fight for, and I took no part or interest in the business. This was Fairfax’s first taste of war at the hands of the enemy, and it must have been decidedly bitter.

We went into bivouac just in front of the town, with headquarters in the village. It seemed as though we had men enough in the encampment to overrun the whole world. If it were not for the numerous trains of wagons needed to supply us, how quickly we could finish up this war. This second bivouac was in all respects similar to the first.

It is reported that General Beauregard, commanding the rebel army, has taken a position just beyond Centreville, and is awaiting our approach, intending to give battle; also that they are strongly intrenched behind breast works and rifle pits.

We are told too, that the woods are full of masked batteries, commanding the roads over which we must march, and it looks now as though we should have some severe fighting in a few hours’ time. It does not yet seem really like war, and it is hard to believe we shall actually have a battle, I suppose one good action will enable us to realize the requirements necessary to make a good soldier, and prove our usefulness, or otherwise, as nothing else will; I hope we may prove equal to the emergency.

Reveille the next morning sounded at daybreak, and soon afterwards we were enroute for Centreville, distant about eight miles; the day was very hot and there was much straggling, many of the men proving poor walkers; at intervals we halted to give time for the advance guard to properly reconnoiter, and also to rest the men, so that we did not arrive in front of our objective point till 1 P. M.; one trouble was the complete blockade of the road by wagons and artillery, obliging the infantry to take to the fields on either side of them, this causing much delay. I was in good condition, and did not mind the fatigue at all. Arriving at Centreville we found no enemy, but a little squalid, wretched place, situated on rising ground overlooking a good deal of the surrounding country. The column turned out to the right and left, forming a line of battle facing almost west, stacked arms, and lay down to await developments. Three regiments of infantry were shortly afterwards sent ahead to reconnoiter, and about a mile in front commenced exchanging shots at long range with the enemy’s pickets; as they advanced, they brought on quite a little fight, in which some of the rebel batteries joined for the first time. We saw the white puffs from the cannon, and watched with breathless interest this first evidence of actual hostilities. Presently an aide came back for reinforcements, and two other regiments were ordered to advance, but had hardly started, when General McDowell coming on the ground, ordered the advance to be discontinued for the present, and the troops withdrawn. We had four men killed outright, and several wounded in this first baptism of fire, which of course, produced great excitement, in the rear, especially when the ambulance with the wounded came in. We knew now there was more to be done than simply marching, and bivouacking, and began to feel a little curious, but still equal to the task, and sure of giving a good account of ourselves. We remained in position the rest of the day and night, watching during the evening the long lines of dust far away to the right and front, which is said to indicate the arrival of reinforcements for the enemy.

This morning we hear the rebel army is posted in a commanding position along the Bull Run stream, deep in many places, but having numerous fords. The rebel general, Johnson, has joined from Winchester, which explains the long dusty lines seen last evening. General McDowell, it is said, intends resting our army for a day or two here, in the mean time ascertaining the exact position of the rebels; we are not at all in need of rest, and I don’t see why we cannot go right ahead, but I suppose it is none of our business to speculate on the conduct of affairs. The wagons are now separately parked, so is the artillery, and the infantry placed so that the color line instantly becomes a line of battle in case of necessity. If the rebs would only come and attack us, how we should warm them.

–The advance column of the National army occupied Fairfax Court House, Va., at eleven o’clock to-day, meeting with no opposition from the Confederates either on the march or in taking possession of the place. Trees had been felled across the road and preparations made at one point for a battery, but there were no guns or troops on the route. The Confederates were drawn up beyond the town and a battle was expected, but as the National forces pressed on they retreated. The cavalry followed them some miles toward Centreville, but the heat of the weather and the previous long march prevented the infantry following. The abandonment of the village by the Confederates was so sudden that they left behind them some portions of their provisions, intrenching tools, and camp furniture. The army advances in three columns, one on the Fairfax road, and the others to the north and south of the road. The advance will be continued to Centreville, eight miles beyond Fairfax, where the Confederates will probably make a stand if they design attempting to hold Manassas Junction. The only casualties reported by Gen McDowell are an officer and three men slightly wounded.–(

–The advance column of the National army occupied Fairfax Court House, Va., at eleven o’clock to-day, meeting with no opposition from the Confederates either on the march or in taking possession of the place. Trees had been felled across the road and preparations made at one point for a battery, but there were no guns or troops on the route. The Confederates were drawn up beyond the town and a battle was expected, but as the National forces pressed on they retreated. The cavalry followed them some miles toward Centreville, but the heat of the weather and the previous long march prevented the infantry following. The abandonment of the village by the Confederates was so sudden that they left behind them some portions of their provisions, intrenching tools, and camp furniture. The army advances in three columns, one on the Fairfax road, and the others to the north and south of the road. The advance will be continued to Centreville, eight miles beyond Fairfax, where the Confederates will probably make a stand if they design attempting to hold Manassas Junction. The only casualties reported by Gen McDowell are an officer and three men slightly wounded.–(