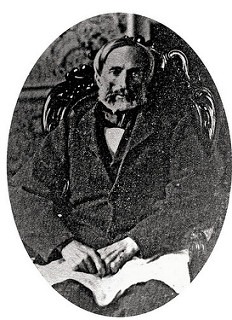

Journalist, editor, publisher, and prolific novelist, John Beauchamp Jones is best known today for his wartime diary, published after the war as A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital and used as an important primary source in studies of the Confederacy and the Civil War.

Journalist, editor, publisher, and prolific novelist, John Beauchamp Jones is best known today for his wartime diary, published after the war as A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital and used as an important primary source in studies of the Confederacy and the Civil War.

A well-connected literary editor and political journalist in the two decades before the war, Jones was able to secure a post as a senior clerk in the Confederate War Office. With entries for every day of the war and his position as a high-level War Office clerk, his diary provides an extraordinary perspective of the Confederacy. Jones quotes dispatches, reports, letters, confidential files and command-level conversations, some of which are not documented anywhere else.

John Beauchamp Jones was born on March 6, 1810, in Baltimore, Maryland, to Captain Joshua Jones, one of the defenders of Baltimore during the War of 1812, and Mary Ann Sands. Financial losses overtook the family and prompted a move to Cyanthia, Harrison County, Kentucky in about 1815.1 His parents both died in Kentucky, Joshua on July 8, 18332 and Mary Ann on August 23, 1861.3

Some of John’s early life, spent in Kentucky and Missouri, was the basis for much of his fiction.4 Traveling to Missouri in about 1826 with his brothers, Caleb 5 and Joshua, they later opened the first mercantile store in New Philadelphia (soon to be renamed Arrow Rock), Missouri. Flooding had taken a heavy toll on early arrivals to the Boonslick region who had settled along the waterways. In early 1829, a town to be named “Philadelphia,” was platted high above the flood waters, near a feature known as the Arrow Rock.6, 7

Stories and books written by Jones drew upon his experiences as an early settler in Missouri’s Boonslick region and as a business owner in Arrow Rock. For example, prominent local residents such as John S. Sappington, a wealthy landowner and physician who had become famous for his quinine-based antimalarial medicine, and the artist George Caleb Bingham, who displayed a preliminary sketch of the “County Election” are mentioned in Jones‘s Life and Adventures of a Country Merchant (1854).8

At one period or another, all of America was in the frontier stage, where conditions demanded a type of business more varied than that in settled areas. “When such a store appeared in a new community, farmers no longer found it imperative to spin their own clothing, to rely on handmade, crude tools, or even to produce all the foodstuffs essential to existence. They were now able to concentrate on the production of those crops which offered the greatest return on the investment.”9 The merchants in the new settlements were frontier capitalists and, often, very influential. In the preface to his novel, The Western Merchant, drawing from his own frontier mercantile experiences, Jones writes — under the pseudonym of Luke Shortfield,

He is … the agent of everybody, and familiar with every transaction in his neighborhood. He is a counselor without license, and yet invariably consulted, not only in matters of business, but in domestic affairs…. Every item of news, not only local, but from a distance,–as he is frequently the post-master, and the only subscriber to the newspapers,– has general dissemination from his establishment, as from a common centre; and thither all resort, at least once a week, both for goods and for intelligence.

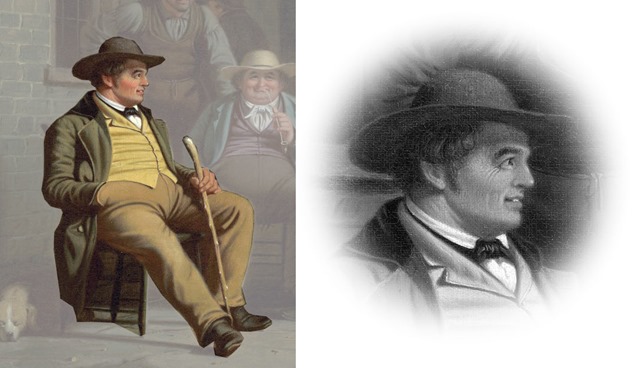

In Arrow Rock, John B. Jones became friends with genre painter of the frontier and Missouri Whig politician, George Caleb Bingham. Bingham is featured in Jones’s novel, The Life and Adventures of a Country Merchant (1854):

Colonel Hopkins, speaking to Nap Wax: “If she (Polly) was a man, she’d be another Missouri artist like Bingham. He’s to paint your town on election day. He’ll have you in it, and me too, with my pot-belly. Perhaps Polly may be there. Daniel Thornton, Squire Nix, Adam Steele, Brother Keene, Mr. Darling, Sam Marsh, Jack Grove, Jackson Fames, Tom Hazel, Jno. Smith, and my cider-man, Black Bob, will all be in it. I’ve seen the first sketch of it, and it’ll be a famous picture.”

“Will he have the tavern and my store in it?”

“Oh yes, and it’ll be better than an advertisement.”

“But he mustn’t paint the confounded Jew’s store!”

“Why not ? Oh, he’ll put down every thing as it is, I’ll warrant you. It’ll be as natural as life itself. He has the genius to do it…

Bingham may have reciprocated. According to Robin Grey, in Bingham’s famous election “genre” studies, Jones is the seated figure on the left in the painting Canvassing for a Vote (1851—52), below.10

Returning east, Jones wrote fiction and various newspaper articles. He may also have acted as a purchasing agent for his brother Caleb. In a 1930s family history, Caleb’s grandson William Justin McCarthy wrote of his grandfather, “He conducted both a wholesale and a retail business. Several of his brothers were stationed in Philadelphia and they watched the markets, bought the supplies and sent them to Boonville, where they were sold again by Caleb Jones.”11

Jones was in Baltimore, Maryland, at least by the middle of 1839, when he had an exchange of correspondence with Edgar Allen Poe, about the time Poe became the assistant editor of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine in Philadelphia. On August 6, he wrote Edgar Allen Poe, informing him that he had been criticized by The Sun and other newspapers of the city. Poe replied on August 8.12

Jones, like many other American authors, including Poe, saw the lack of international copyright protection as a barrier to publication by American authors, limiting financial opportunities for writers.13 The November 1839 issue of Burton’s included Thoughts on the Literary Prospects of America,” an essay by “J. Beauchamp Jones, Philad.” In the essay, Jones discusses that the lack of a good copyright law limits the opportunities for American writers when American publishers pirate European works with impunity.14

The following month’s issue of Burton’s, December, included a short story by “J. Beauchamp Jones, Philad.” entitled “The Lump of Coal.”15

A friend, Baltimore-area socialite Sally Cable Parsons, introduced Jones to her niece, Frances Thomas Custis, sometime before 1840. On October 16, 1839, J. B. Jones (of Baltimore) sent a marriage proposal letter to Miss Francis Custis of Drummond Town, Accomac, Co., Virginia, requesting that her reply be sent to Beauchamp Jones as there were several John Jones in Baltimore.16 They were married on April 13, 1840, in Accomac County.17 Jones’s marriage into the politically connected Virginia slave-holding family influenced both his fiction and newspaper career.

Of Frances Custis, Civil War scholar James I. Robertson, Jr., says:18 “A product of Virginia’s Eastern Shore aristocracy, Miss Custis claimed an ancestry that included marital ties to George Washington.19 Prominent statesmen John Tyler and Henry A. Wise also had close connections with the Custis family. Two of Frances’s brothers controlled the family estate in Accomac County. Their generosity to their sister was regular and large… The couple married late that year. Jones was thirty; his wife, a year older. Marriage catapulted Jones into the high circle of Virginia’s political elite. Henry A. Wise, master of the Eastern Shore and founder of the Virginia branch of the Whig Party, befriended the Baltimore writer.” Wise was a cousin of Frances’s mother, Nancy Parsons Custis.

At some point in 1840, the new couple moved to Philadelphia. Their address was Mr. J. B. Jones, 124 So. 9th, Philadelphia, Pa.20

When he could not find a publisher to “examine” his first novel, Wild Western Scenes, Jones became the “joint proprietor and editor” of the Baltimore Saturday Visiter, a popular weekly newspaper, on May 9, 1840. His novel was subsequently published in serial format in the Visiter. On November 8, 1841, Jones resigned as editor of the Visiter,21 selling his stake to Joseph Evans Snodgrass.22

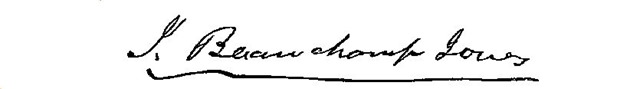

Jones was included in the second of three installments of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Autography,” published in Graham’s Magazine from November 1841 to January 1842. Poe’s plan “was to accompany autograph signatures of the famous and the obscure literati with comments on individual character, as suggested by relevant features of chirography. Appended to each autograph was literary gossip that spiced the critical commentary on each author’s writings.”23

Mr. J. Beauchamp Jones has been, we believe, connected for many years past with the lighter literature of Baltimore, and at present edits the “Baltimore Saturday Visiter,” with much judgment and general ability. He is the author of a series of papers of high merit now in course of publication in the “Visiter,” and entitled “Wild Western Scenes.”

His MS. is distinct, and might be termed a fine one; but is somewhat too much in consonance with the ordinary clerk style to be either graceful or forcible. 24

Late in 1841, Jones became the editor of the party organ 25 of President John Tyler’s administration, the Daily Madisonian newspaper, where he remained until 1845, when Tyler left office, 26 with Jones enjoying close ties with several members of the administration.27

Late in September, 1841, Tyler told a friend, “The Madisonian is the official organ and is now enjoying the Executive patronage.” Two months later, Jones proclaimed the special status of his paper as the “Official Organ of the Government,” writing that the paper was dedicated to “publishing officially the proceedings of the Government, and cherishing and defending honestly and earnestly the principles upon which the public acts of President Tyler have thus far been founded.” A year later, Jones wrote that the “views and purposes of the Administration will, as heretofore, be made known through the columns of this paper.” Some surviving records demonstrate instances where Tyler gave specific instructions to Jones on what to write.28

(President Tyler’s)…organ was “The Madisonian,” a newspaper originally established by Thomas Allen, under the auspices of William C. Rives, James Garland, and other recusant Democrats in Congress, who declared for “Conservative” doctrines, and succeeded in diverting the Congressional printing to that establishment. Allen sold out to John B. Jones. In those days it was everywhere said that Jones was of the “War Office.” This was a mistake. Others declared that he was a myth. Notwithstanding such annunciations, he was an actual, breathing man. He scarcely did anything but write editorials about the “brewing storm,” and “justice to John Tyler.” He was the author of “Wild Western Scenes,” a work which was far more popular than his newspaper.

This gentleman was of an amiable disposition– kind and liberal to the persons in his employ, and deservedly respected by all who knew him.29

John Beauchamp Jones lived most of his life in the “border” slave states of Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. His anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, views — not unusual for the mid 19th century — are readily found in his fiction, which, however, do little to show his views on slavery, though slaves were owned by both his family in Missouri 30 and his wife’s family in Virginia. In his writings towards the possible annexation of Texas in the Daily Madisonian, though, he was blunt, denouncing abolitionists and the critics of annexation as fanatics and traitors, holding that encouraging the “fatal principle” of abolitionism “is to prepare the way for the incursions of a foreign enemy,” Great Britain, which had “proclaimed to the world that, in negotiating a treaty with Texas, the design is to procure the abolition of slavery in the United States.” Jones felt it incomprehensible that any politician or publicist would refuse to sanction the institution — slavery — that the administration considered a vital safeguard of prosperity and harmony. “It is to the cotton crops of the South, and the kind of labor employed in their production, that our country is indebted for the maintenance of peace with the only country from which we have anything to dread on the score of power.” American security was guaranteed by cotton and the slave labor that produced it, he held.31

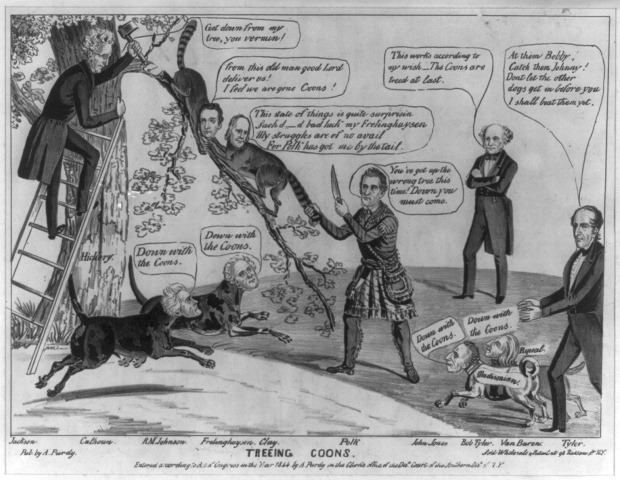

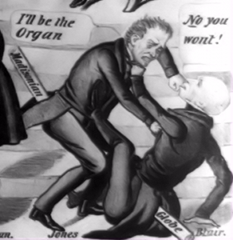

Jones appears in two political satire cartoons surviving from 1844. In one he portrayed as one of four dogs participating in the treeing of “coons” Henry “that old coon” Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen. Clay was the 1844 Whig candidate for President and Frelinghuysen was his running mate for vice president. 32

Jones appears in two political satire cartoons surviving from 1844. In one he portrayed as one of four dogs participating in the treeing of “coons” Henry “that old coon” Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen. Clay was the 1844 Whig candidate for President and Frelinghuysen was his running mate for vice president. 32

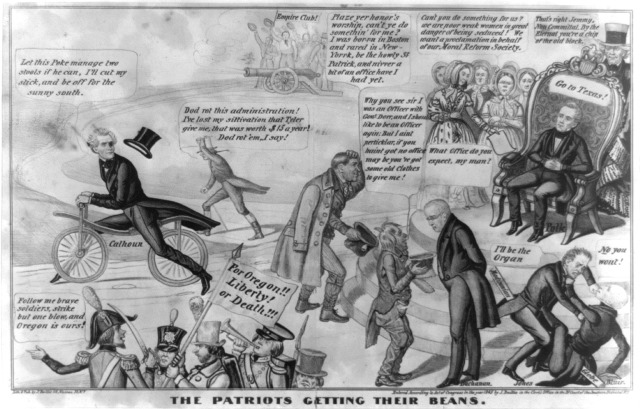

The second cartoon is from after the election of 1844, where James K. Polk was the victor. In it, Polk is seated in the Presidential Chair “his hands folded and below him and apparently oblivious to the activity around him… Below him John Beauchamp Jones and Francis Preston Blair, editors of influential rival newspapers, the ’Madisonian’ and the ‘Globe,’ fight for the privilege of being the administration organ.”33 Polk was plagued throughout his four-year administration with people seeking government jobs or patronage.

The second cartoon is from after the election of 1844, where James K. Polk was the victor. In it, Polk is seated in the Presidential Chair “his hands folded and below him and apparently oblivious to the activity around him… Below him John Beauchamp Jones and Francis Preston Blair, editors of influential rival newspapers, the ’Madisonian’ and the ‘Globe,’ fight for the privilege of being the administration organ.”33 Polk was plagued throughout his four-year administration with people seeking government jobs or patronage.

After the end of the Tyler Administration in 1845, Jones continued publication of the Madisonian until it was bankrupted later that year. In the early days of the Polk administration, Secretary of State James C. Calhoun offered Jones a post as charge d’affaires in Naples. While Jones had great respect for Calhoun, he declined. One of the few prized possessions he took with him in his flight to the South in 1861 was a “fine old portrait of Calhoun, by Jarvis.”34

Over the next several years, along with a brief trip to Europe in 1846, Jones was a “full-time” writer, producing Book of Visions (1847), Rural Sports: A Tale (1849), The Western Merchant (1849), The City Merchant (1851), The Spanglers and the Tingles; or, The Rival Belles (1852), The Monarchist (1852), Adventures of Col. Gracchus Vanderbomb (1852), Freaks of Fortune (1854) Life and Adventure of a Country Merchant (a rewrite of Western Merchant, changing from first-person to a third-person narrative, 1854), The Winkles (1855), The Warpath (1856), and The Border War: A Tale of Disunion (serialized in the Southern Monitor in 1857, published in book form in 1859,35 and revised and republished in 1861 as Secession, Coercion, and Civil War: The Story of 1861).

Jones was one of nearly a thousand delegates assembled for the Southern Commercial Convention at Savannah, Georgia in December 1856, with an open letter, “Southern Presses at the North” published as Appendix 7 of the convention proceedings.36

John B. Jones, a Southern sympathizer from New Jersey, suggested a novel scheme for spreading Southern propaganda. He proposed the establishment of four daily journals in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, to act as publicity agents for Southern institutions and as an espionage bureau to detect unfriendly writers, business men and societies and expose them to the judgment of slave holders.37

After his proposal to the convention was ignored, Jones circulated a prospectus for establishing a Southern-leaning newspaper in the North. In 1857, when no takers came forward, at his own expense, Jones established the Southern Monitor in Philadelphia to be “a Southern Organ in the North,” with the first issue published June 6th.

The SOUTHERN MONITOR will defend the decision and opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case; and it will advocate the Constitution and the Union on the terms and stipulations agreed to by our forefathers. It will support the Democracy, the only national party now in existence; and it will not be sectional in being Southern; for nowhere else but in the South is the Constitutional and Union party unequivocally in the ascendancy. Its mission will be to combat Black Republicanism, and to repel assaults on Southern rights and Southern institutions. And that it may be effective, the cooperation of Southern men, and friends of the South wherever they may dwell, is earnestly invoked.38

In the first issue, Jones declared his paper’s defence of Southern rights and Southern institutions will be firm and uncompromising.” While his paper was published in the North for a Southern audience, it was also “with an eye to explaining Southern positions to Northerners, and to proclaiming the South as most representative of American constitutional values.”39 His bold public statements on southern rights drew criticism from northern editors.40 However, circulation grew to the point that the Southern Monitor was reasonably self-sufficient and, with it, Jones became an “increasingly controversial figure in Philadelphia.” A friend in Burlington, New Jersey advised him to leave town, but Jones refused. He felt his work might help avert a possible war, the family had a comfortable home in Burlington and, between his books and his wife’s property on the Eastern Shore, the family was doing well financially.41

In the days and weeks leading up to war, Jones “was one of the few people who envisioned the struggle as the large-scale, all-consuming war it became.”42 Despairing of any secession movement by his home state, Maryland, or his wife’s home state, Virginia, Jones wrote a personal letter to President Jefferson Davis on March 28, 1861, seeking a civilian appointment in the new Confederacy, hopefully a position where he could occasionally contribute to newspapers for the southern cause.43, 44, 45 A letter from diplomat Ambrose Dudley Mann to Jones promising support was enclosed.46

In his first diary entry, Jones writes:

April 8th, 1861. Burlington, New Jersey.–The expedition sails to-day from New York. Its purpose is to reduce Fort Moultrie, Charleston harbor, and relieve Fort Sumter, invested by the Confederate forces. Southern born, and editor of the Southern Monitor, there seems to be no alternative but to depart immediately. For years the Southern Monitor, Philadelphia, whose motto was “The Union as it was, the Constitution as it is,” has foreseen and foretold the resistance of the Southern States, in the event of the success of a sectional party inimical to the institution of African slavery, upon which the welfare and existence of the Southern people seem to depend. And I must depart immediately; for I well know that the first gun fired at Fort Sumter will be the signal for an outburst of ungovernable fury, and I should be seized and thrown into prison.

I must leave my family–my property–everything. My family cannot go with me–but they may follow. The storm will not break in its fury for a month or so. Only the most obnoxious persons, deemed dangerous, will be molested immediately.

On April 9, fearing the imminent onset of hostilities, Jones set out for the south arriving in Richmond, Virginia, on April 12, where he was to remain for the next month. His wife and children remained in Burlington for several weeks, and finally rejoined him in late May.47

On the 15th, he learned “…from the Northern exchange papers, which still came to hand, that my office in Philadelphia, ‘The Southern Monitor,’ had been sacked by the mob. It was said ten thousand had visited my office, displaying a rope with which to hang me.48 Finding their victim had escaped, they vented their fury in sacking the place. I have not ascertained the extent of the injury done; but if they injured the building, it belonged to H. B., a rich Republican. They tore down the signs (it was a corner house east of the Exchange)49, and split them up, putting the splinters in their hats, and wearing them as trophies.”50

While Jones had powerful connections politically, socially and through his wife’s family, he was not inclined to seek a political position, especially in the new Southern administration, writing on May 5th, 1861, “I could not hope for any commission as a civil officer, since the leaders who have secured possession of the government know very well that, as editor, I never advocated the pretensions of any of them for the Presidency of the United States. Some of them I fear are unfit for the positions they occupy.”51

On May 5th, 1861, in Richmond, Virginia, former US President John Tyler provided a document to Jones, a “memorial” to be delivered to Jefferson Davis, signed by Tyler and many of the members of the Virginia secession convention, asking for appropriate civil employment for Jones in the new government.52 Jones was also provided a letter of recommendation by his wife’s first cousin, once removed,53 former Virginia governor Henry A. Wise.54

Jones was subsequently offered, and accepted, a Confederate War Office position as a clerk in what became the passport office. The September 1866 DeBow’s Review said of Jones, in its Editorial Notes, “All who had business with the departments will remember him as the indefatigable chief of the Passport Office, from which his opportunities of observation and information were of consequence very great. He has availed himself of this in his work, and furnishes much in relation to the secret history of the government.”55

John Beauchamp Jones’s diary, from the beginning, was written with the intent of eventual publication56 and “with the knowledge, if not the approval, of the secretary of war and of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. It was written at the time of events, but edited shortly after the war ended.”57 While Jones tried to be accurate and balanced, there are inaccuracies, inconsistencies and prejudices, such as his anti-Semitism, in his work. However, for the most part, the diary is a worthy accounting of the workings of the Confederate government and its War Department.58

Like many families that resided in the border states, John B. Jones and his surviving brothers — Joshua, had died in 1846 — were split between the North and the South. From Oakland, Missouri, on August 25, 1861, Jones’s sister-in-law, Nancy Chapman Jones, wife of Caleb, wrote in a letter to daughter, May, 59

Richard and Robert Jones are both Union men. Robert was shot by a secessionist and badly wounded; he to recovering. William is a rebel he was arrested and taken to Jefferson City, where he was detained a few days, and then released without any trial. Ben went to Kentucky about two months since, I doubt if he ever makes this his home again. John is ultra southern, and your pa is marked as a rebel, he denies the right of secession, but thinks our grievances justify rebellion and revolution. Truly this is a fratricidal war brother against brother, that we my soon have peace with an honorable adjustment of all our difficulties is my prayer.

Caleb himself was almost killed on one occasion, 60, 61

Some of the home guard come out here for oats. Mr. Jones was in the garden, and one of them laid his gun on the fence and took deleberate aim at him, but fortunately missed him. Mr. Jones inquired why they shot at him, they said he did not halt when they commanded him, and he had not heard any order to halt, the discharge of the gun was the first intimation I had of their being on the place, so you may form some idea of the state of things here.

Caleb Jones and friend Dr. George W. Main were apparently marked men. Although a native of Scotland and still a British subject, Dr. Main was arrested on August 14, 1862, as a suspected Southern sympathizer. His body was found later in the Missouri River. 62, 63 With the very real threat they would become victims of the Missouri guerilla warfare, Caleb and Nancy Jones, by September 1864, fled Missouri and escaped to Paris Station, Canada. 64

During the war, John Beauchamp Jones supported the Southern cause to the bitter end. However, he was highly critical of many Southern politicians, officers, and officials, including Jefferson Davis’s performance as president.

During the war, John Beauchamp Jones supported the Southern cause to the bitter end. However, he was highly critical of many Southern politicians, officers, and officials, including Jefferson Davis’s performance as president.

Following the war, he moved North, where he died from tuberculosis, February 6, 1866, less than a year after the end of the war in Burlington, New Jersey. Before his death, Jones had edited his diary and delivered it to J. B. Lippincott & Co. in Philadelphia. When his diary was published, many southerners reacted with contempt.

In July, 1866, The Athenæum, a British literary journal published a multi-page review of John Beauchamp Jones’s final work:65

After the shoals of worthless books about the American war that have appeared during the last five years, it is a pleasure to open a thoroughly entertaining and, in some respects, very instructive work on a subject that has occasioned so much poor and profitless writing. This Diary is no work of fancy, but a genuine record of four years labour and sad experience, by a man who, from April, 1861, until the fall of Richmond in April, 1865, lived in the highest grade of the official world of the Confederate States–working at the same desk with such men as Major Tyler and Mr. Benjamin; holding constant intercourse with Mr. Jefferson Davis and the members of his cabinet; watching with critical eye the struggles of parties and the sufferings of the multitude; and recording, with a view to future publication, the gossip of cliques, the rumours of offices, and the trials of a capital–in which famine was doing insidious work at a date when the Confederate sympathizers in London were under the impression that their friends in Richmond were abundantly provided with the necessaries of life. Nor was Mr. Jones less fitted by ability than by position to become the diarist of life at the seat of the Confederate Government. A journalist and writer of books, who had steadily advocated the policy of the slave-owners, the fugitive editor of the ‘Southern Monitor’ (Philadelphia) possessed the literary qualifications for the task which he undertook as soon as the temporary rupture of the Union had been effected.

1. Culpepper, Marilyn Mayer; Women of the Civil War South: Personal Accounts from Diaries, Letters and Postwar Reminiscences; McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2003, pp 120

2. Johnson, William Foreman, History of Cooper County, Missouri; Historical Publishing Company, Topeka, Cleveland, 1919, pp 916

3. Letters of Nancy Chapman Jones, wife of Caleb Jones, to their daughter, May Jones McCarthy, posted online by Nan O’Meara Strang at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Military/Jones_Letters.pdf, accessed 5/9/2016

4. Christensen, Lawrence O. , William E. Foley, Gary Kremer; Dictionary of Missouri Biography, by , University of Missouri Press, 1999.

5. Geiger, Mark W.; Missouri’s Hidden Civil War: Financial Conspiracy and the Decline of the Planter Elite, 1861-1865; Doctoral Program dissertation, Graduate School, University of Missouri-Columbia; May 2006 “There was little old money in the Boons lick, so humble origins were not a drawback to rising socially. The career of Caleb Jones, of Boonville in Cooper County, shows this pattern of occupational change and upward mobility. Jones came originally from Baltimore, and when he was ten his family moved to Cynthiana County, Kentucky. In 1826, when he was twenty-one, Jones came to Missouri on horseback, swimming his horse across the Missouri River at Franklin. Acquiring stock on credit, Jones opened a store at the landing at Arrow Rock, upriver from Franklin and Boonville. His affairs prospered, and in the normal course of business he routinely extended medium-term credit to his customers. In time this led to banking, and Jones became one of the pioneer bankers in the Boonslick. He also invested in real estate an d eventually owned six thousand acres in Cooper County. By 1861, Jones had amassed money to sell his banking and mercantile interests and become a gentleman farmer. Despite his strong southern sympathies, Jones took no part in raising money for the southern volunteers in 1861 and 1862, or at least not to the extent of risking his own property. He died in 1883, reportedly the richest man in Cooper County.”

6. Phillips, Authorene Wilson; Arrow Rock: The Story of a Missouri Village; University of Missouri Press, 2005; pp. 48-54 “According to (historian) Charles van Ravenswaay, when John Beauchamp Jones and his brother Joe came west to ‘Philadelphia’ from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1830 to set up the first grocery store, the only residents of the village were a Canadian trapper who had worked for General William Henry Ashley’s company and his wife living in a mud shanty, and a ‘family from Virginia living in a log house with their slaves in a row of huts.’ Jones, an aspiring writer who used the pen name Luke Shortfield, recorded what he saw on the Missouri frontier. This was later included in a book of fiction, but his description rings true for the New Philadelphia of 1831.” (Note: John Beauchamp Jones had 6 brothers, but none of them were named Joe. As Luke Shortfield was a pseudonym for John B. Jones, Joe was likely a pseudonym for one of his brothers, possibly Caleb. — M. P. Goad, 5/11/2016)

7. Missouri — A Guide to the “Show Me” State; Compiled by Workers of the Work Project Administration in the State of Missouri; American Guide Series; Sponsored by The Missouri State Highway Department; Published by Duell, Sloan, and Pierce, New York, 1941, page 357— “On May 23, 1829, a town was laid out and called New Philadelphia, until the derision of the inhabitants for such an imposing name caused the older one (Arrow Rock) to be resumed in 1833. Growth was slow, and when, in the spring of 1830, John Beauchamp Jones established the first store here, the village site was a tangle of ‘bushes, brushes and trees.’ The only residents were a Canadian-French employee of General Ashley’s fur trading company, who, with his American wife, occupied an 8-by-10 foot ‘mud shanty’ and ‘an amiable’ family from Virginia, living in a log house with their slaves in a row of huts. As the back country was settled, the town became a thriving river port.”

8. Christensen, Lawrence O. , William E. Foley, Gary Kremer; Dictionary of Missouri Biography, by , University of Missouri Press, 1999.

9. Atherton, Lewis E.. 1937. “The Services of the Frontier Merchant”. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24 (2). [Organization of American Historians, Oxford University Press]: 153—70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1892076.

10. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press). Grey states in note 4. “This is my own attribution based on photographs of J. B. Jones from various archives. Although other figures in the painting have been identfied, this figure has not. It is noted, moreover, in Paul C. Nagel’s George Caleb Bingham that Jones’s autobiographical character Nap Wax (in Life and Adventures of a Countr y Merchant) was told that every citizen in the town was likely to be in the picture or in the Election Series: ‘Me, too, with my pot-belly. I’ve seen the first sketch of it, and it ’ll be a famous picture . . . better than an advertisement.’ For a biography and attribution of figures in paintings, see John Francis McDermott and Albert Christ-Janer.”

11. McCarthy, William Justin; Family history by McCarthy, grandson of Caleb and Nancy Jones, written in the 1930s, posted online at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Biographical/Boonville_McCarty.pdf, accessed 5/10/2016

12. Poe, Edgar Allen to John Beauchamp Jones, August 8, 1849

13. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press)

14. Jones, John Beauchamp; “Thoughts on the Literary Prospects of America;” Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine and American Monthly Review, Volume 5; November 1839, pp. 267-270. (Burton’s was edited by William E. Burton and Edgar Allen Poe at this point.)

15. Jones, John Beauchamp; “The Lump of Coal;” Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine and American Monthly Review, Volume 5; December 1839, pp. 305-308. (Burton’s was edited by William E. Burton and Edgar Allen Poe at this point.)

16. Musser, Charles; Bickelman GEDCOM; Genealogy Forum.com; file gedr7012.ged; file date 08/03/97; downloaded for reference 05/06/2016

17. Miles, M. K.; MilesFiles online genealogy, 100’s of Families from the Eastern Shore, Virginia Eastern Shore Public Library (accessed 5/6/2016). Citations for Jones and Custis marriage:

[S558] Nora Miller Turman, Accomack Co, VA, Marriage Records, 1776-1854 (Recorded in Bonds, Licenses and Ministers’s Returns).

[S2066] Nora Miller Turman, Nora Miller Turman’s Genelaogy Research Files, Selby File Folder (information provided by Miss Ruth V. Greer, 2904 23rd Street, Parkersburg, WV 26101, from the 1980s).

18. Robertson, James I., Jr.; Editor’s Preface; A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Vol. 1 April 1861-July 1863, John Beauchamp Jones, University of Kansas Press, 2015, page ix

19 Frances Thomas Custis’s ancestry that “included marital ties to George Washington” was actually first cousin, thrice removed to Daniel Park Custis, first husband of Martha Dandridge. After Daniel’s death, Martha married George Washington. [Prominent Family Connections of Frances Thomas Custis, Wife of John Beauchamp Jones (as determined by M. P. Goad through review of various genealogical references)]

20. Musser, Charles; Bickelman GEDCOM; Genealogy Forum.com; file gedr7012.ged; file date 08/03/97; downloaded for reference 05/06/2016

21. Thomas, Dwight Rembert; Poe in Philadelphia, 1838-1844: A Documentary Record, Part 1; University of Pennsylvania., 1978.

22. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press)

23. Ljungquist, Kent P.; “Poe’s ‘Autography’: A New Exchange of Reviews;” American Periodicals; Vol. 2 (Fall 1992), pp. 51-63; Ohio State University Press.

24. Poe, Edgar Allen; “A Chapter on Autography;” Graham’s Magazine; Vol. XIX., No.6; Philadelphia: December, 1841; page 282.

25. Party newspapers, referred to sometimes as “the party organs,” would play prominently in 19th-century efforts to promote rhetorical and policy differences between the parties and to connect mass publics to these circles of elite thought. (The Democratic Party: Documents Decoded, Douglas B. Harris, Lonce H. Bailey, ABC-CLIO, 2014, page xvi)

Often, the “organs” of the party in power were funded through government resources and, at times, were the printers contracted to print government publications.

26. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press)

27. Byrne, Frank J.; “The Literary Shaping of Confederate Identity: David R. Hundley and John Beauchamp Jones in Peace and War;” Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas; Lesley J. Gordon, John C. Inscoe; LSU Press, 2007

28. Ellis, Richard J., Speaking to the People: The Rhetorical Presidency in Historical Perspective, Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1998, page 76

29. Gobright, Lawrence Augustus, Recollection of Men and Things at Washington, During the Third of a Century, pub. Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1869, page 57

30. McCarthy, William Justin; Family history by McCarthy, grandson of Caleb and Nancy Jones, written in the 1930s, posted online by Nan O’Meara Strang at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Biographical/Boonville_McCarty.pdf, accessed 5/10/2016, “Mother often said she never did any work until after the war. Grandpa (J.B. Jones’s brother, Caleb) was always very kind as a master. He did not buy and sell slaves for profit, but he always had enough to supply the needs of the family, and when my mother married and lived in San Antonio, Texas, the same order prevailed there, so there was no need for her to do anything.”

31. Hietala, Thomas R.; Manifest Design: American Exceptionalism and Empire; Cornell University Press, 2003; page 25

32. Bucholzer, H; Treeing Coons; N.Y. : Pub. by A. Purdy, 1844. Library of Congress image — Summary: One of the few satires sympathetic to the Democrats to appear during the 1844 presidential contest. Democratic presidential nominee James Polk is portrayed as a buckskinned hunter who has treed “coons” Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen. (Clay’s nickname “that old coon” had wide currency in the campaign.) Holding a knife in his left hand, Polk grasps the Clay coon by the tail, saying “You’ve got up the wrong tree this time! Down you must come.” At left former President Andrew Jackson stands on a ladder leaning against the “Hickory” tree and chops at the branch holding the two Whigs. He exclaims “Get down from my tree you vermin!” Frelinghuysen says, “from this old man good Lord deliver us!” Clay adds in verse: The state of things is quite surprisin. / Such d–d bad luck my Frelinghuysen. / My struggles are of no avail / For Polk has got me by the Tail. Two other Democrats, John C. Calhoun and Richard M. Johnson, appear as dogs rushing in from the left, saying, “Down with the Coons.” Another Democratic ex-President, Martin Van Buren, watches from the right, remarking, “This works according to my wish–The Coons are treed at last.” In the right foreground incumbent President John Tyler sets his dogs on the coons, saying, “At them Bobby! Catch them Johnny! Dont let the other dogs get in before you I shall beat them yet.” His dogs are son Robert Tyler (labeled “Repeal” for his activism on behalf of the Irish Repeal movement) and John Beauchamp Jones, editor of the newspaper the “Madisonian,” organ of the Tyler administration. They also chant, “Down with the Coons.”

33. Clay, Edward Williams (attribution by Library of Congress); Lithography and publication by James Baillie, 1845; Library of Congress image — Summary: A satirical view of the scramble among newly elected President James K. Polk’s 1844 campaign supporters, or “patriots,” for “their beans,” i.e., patronage and other official favors. Polk (upper right) sits in the Presidential Chair, his hands folded and apparently oblivious to the activity around him. From behind the chair Andrew Jackson prompts him, “That’s right Jemmy, Non Committal. By the Eternal you’re a chip of the old block.” To Polk’s right a group of homely women present a petition and ask, “Can’t you do something for us? we are poor weak women in great danger of being seduced! We want a proclamation in behalf of our Moral Reform Society.” Below him John Beauchamp Jones and Francis Preston Blair, editors of influential rival newspapers, the “Madisonian” and the “Globe,” fight for the privilege of being the administration organ. In the center an Irishman, hat in hand, approaches Polk and asks, “Plaze yer honor’s worship, can’t ye do somethin’ for me? I was bor-r-n in Boston and rared in New-Yor-r-k, be the howly St. Patrick, and nivver a bit of an office have I had yet.” Nearby, a German or Dutchman walks away in disgust shouting, “Dod rot this administration! I’ve lost my sittivation that Tyler give me, that was worth $15 a year! Dod rot ’em, I say!” In the foreground Secretary of State James Buchanan asks a small, ragged figure, “What Office do you expect, my man?” The man, a Rhode Islander, responds, ” . . . I was an Officer with Govr. Dorr, and I should like to be an Officer agin; but I ain’t perticklar, if you haint got no office may be you’ve got some old Clothes to give me!” Dorr was the leader of an abortive revolution in Rhode Island in 1842. (See Trouble in the Spartan Ranks, no. 1843-6). At left South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, a frustrated aspirant for the 1844 Democratic nomination, rides off on a velocipede saying, “Let this Poke manage two stools if he can, I’ll cut my stick, and be off for the sunny south.” Above, in the background, members of the “Empire Club” wave their hats and fire a cannon. They may represent the expansionist platform on which Polk campaigned, which many Whigs feared would provoke war with Mexico. In the left foreground is a motley militia troop carrying a banner “For Oregon!! Liberty! or Death!!!” Their leader proclaims, “Follow me brave soldiers, strike but one blow, and Oregon is ours!” Polk’s campaign platform favored reannexation of the Oregon Territory.

34. Aiken, David; Forward to Blood Money – The Civil War and the Federal Reserve, by John Remington Graham; Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, Louisiana 2011.

35. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not 3 Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press)

36. “Appendix to Convention Proceedings;” Debow’s Review, Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources; Southern Convention at Savannah [Volume 22, Issue 3, Mar 1857; pp. 307-318]

37. Wender, Herbert, “The Southern Commercial Convention at Savannah, 1856;” The Georgia Historical Quarterly; Vol. 15, No. 2 (JUNE, 1931), page 186

38. A Southern Organ in the North, advertisement from DeBow’s Review, June 1857.

39. Grey, Robin Sandra , “Patronage, Southern Politics, and the Road Not 3 Taken: Poe and John Beauchamp Jones;” Essay published in Poe Writing/Writing Poe, edited by Richard Kopley and Jana Argersinger. AMS Studies in the Nineteenth Century, No. 45, AMS Press (Poe Writing/Writing Poe gathers a handful of “the finest papers” given at the First International Edgar Allan Poe Conference, held in Richmond, Virginia, in October 1999 — Review by Paul C. Jones in the “Edgar Allen Poe Review,” Penn State Press)

40. Byrne; , Frank J.; “The Literary Shaping of Confederate Identity: David R. Hundley and John Beauchamp Jones in Peace and War;” Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas; Lesley J. Gordon, John C. Inscoe; LSU Press, 2007

41. Robertson, James I., Jr.; Editor’s Preface; A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Vol. 1 April 1861-July 1863, John Beauchamp Jones, University of Kansas Press, 2015, page xii

42. Virginia Historical Society Announcement of lecture “The Civil War’s Most Valuable Diarist by James I. Robertson, Jr” (http://www.vahistorical.org/events/programs-and-activities/lectures-and-classes/civil-wars-most-valuable-diarist-james-I; accessed 5/11/2016)

43. The Papers of Jefferson Davis: 1861, LSU Press, Jan 1, 1992, page 83

44. Robertson, James I., Jr.; Editor’s Preface; A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Vol. 1 April 1861-July 1863, John Beauchamp Jones, University of Kansas Press, 2015, page xii

45. Jones, John Beauchamp, Correspondence to Jefferson Davis, dated March 28, 1861; Samuel W. Richey Collection of the Southern Confederacy, Miami University Libraries digital collections, Oxford, Ohio

46. Mann, Abrose Dudley; Correspondence to John Beauchamp Jones; March 26, 1861; Samuel W. Richey Collection of the Southern Confederacy, Miami University Libraries digital collections, Oxford, Ohio.

47. Byrne; Frank J.; “The Literary Shaping of Confederate Identity: David R. Hundley and John Beauchamp Jones in Peace and War;” Inside the Confederate Nation: Essays in Honor of Emory M. Thomas; Lesley J. Gordon, John C. Inscoe; LSU Press, 2007; Note 14

48. War Feeling at the North, The Daily Dispatch: April 18, 1861. Richmond Dispatch. 4 pages. by Cowardin & Hammersley. Richmond. April 18, 1861.

49. Scharf, John Thomas and Thompson Westcott; History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884, Volume 3; L. H. Everts & Company, 1884 – Philadelphia (Pa.), page 2021 — “The Southern Monitor was first published in 1857 in Goldsmith’s Hall, Liberty Street. The office was subsequently removed to the northeast corner of Dock and Walnut Streets, where the paper ended its career in 1860.” (Note: It actually ended April 1861, when Jones fled to the South. The Merchant Exchange Building, which Jones mentions, is still standing. 5/7/2016 — M. P. Goad)

50. Jones, John Beauchamp, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866, page 19

51. Jones, John Beauchamp, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866, page 32

52. Jones, John Beauchamp, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866, page 31

53. Prominent Family Connections of Frances Thomas Custis, Wife of John Beauchamp Jones (as determined by M. P. Goad through review of various genealogical references).

54. Jones, John Beauchamp, A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866, page 31

55. Editorial Notes, “Rebel War Clerk’s Diary;” DeBow’s Review, September 1866, Volume 2, Issue 3, page 334

56. Tucker, Spencer C.; American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [6 volumes]; ABC-CLIO, 2013

57. Wright, Mike; City Under Siege: Richmond in the Civil War, Cooper Square Press, 2002, page 211

58. Tucker, Spencer C.; American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [6 volumes]; ABC-CLIO, 2013

59. Letters of Nancy Chapman Jones, wife of Caleb Jones, to their daughter, May Jones McCarthy, posted online by Nan O’Meara Strang at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Military/Jones_Letters.pdf, accessed 5/9/2016

60. Letters of Nancy Chapman Jones, wife of Caleb Jones, to their daughter, May Jones McCarthy, posted online by Nan O’Meara Strang at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Military/Jones_Letters.pdf, accessed 5/9/2016

61. Culpepper, Marilyn Mayer; Women of the Civil War South: Personal Accounts from Diaries, Letters and Postwar Reminiscences; McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2003, pp 133-134

62. Cisco, Walter Brian; War Crimes Against Southern Civilians; Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, Louisiana, page 29

63. Letters of Nancy Chapman Jones, wife of Caleb Jones, to their daughter, May Jones McCarthy, posted online by Nan O’Meara Strang at Cooper County, Missouri Gen Web http://mogenweb.org/cooper/Military/Jones_Letters.pdf, accessed 5/9/2016 — “I know you will be pained to hear of Dr. Main’s untimely death, some two months since a party of men two of whom were dressed in the federal uniform went to the Dr. house about midnight and by representing themselves as friends gained admitance, and then took the Dr. to the river hung him and threw him in the river his body was recovered the second day after in the same place they had thrown him. He seemed also to have received a blow as one of his eyes was knocked out. Mrs. [Jessie] Main tried to follow him, but they drew a pistol on her and forced her back, the citizens dare not make an effort to ferret out the murderers, because the Dr. was a southern sympathizers, Mrs. Main has been staying with Mrs. Hogan since. Dan Wooldridge, Justinian Williams , A. and D. Lincoln , and Hardige Andrews have gone to Nebraska”

64. Culpepper, Marilyn Mayer; Women of the Civil War South: Personal Accounts from Diaries, Letters and Postwar Reminiscences; McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2003, page 157

65. Francis, John (publisher); The Athenæum, Journal of English and Foreign Literature, Science, and the Fine Arts; London, Saturday, July 14, 1866; pp 41-43; Printed by James Holmes, Took’s Court, Chancery Lane; Published at The Office, 20, Wellington Street, Strand, W.C.