“It was my fortune to be present at the opening scenes of the grand drama of the American civil war.”1

First Scenes of the Civil War

By James Chester2

In December 1860, James Chester was a sergeant in Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment, stationed on Sullivan’s Island, at Fort Moultrie, Charleston Harbor, South Carolina., having just completed his sixth year of military service. Twenty-four years later, still in the Army and an artillery captain, his reminiscences of the events at Moultrie and Sumter as a senior enlisted man were published in The United Service, A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs, limiting himself “strictly to what I find in my memory, facts, and impressions the recollections of which have withstood the erosions of almost a quarter of a century.”

Note: Images in this article are from various sources. The original article in the 1884 issue of The United Service had no images.

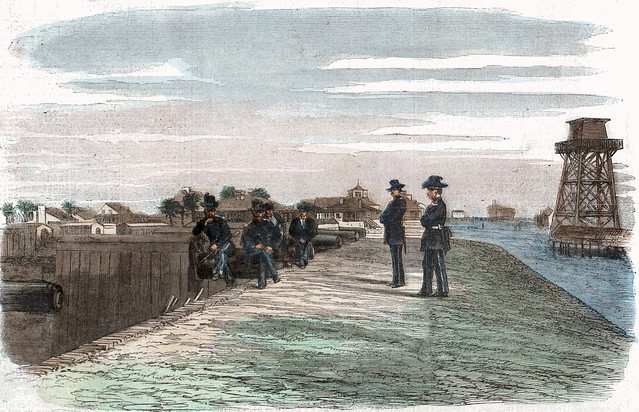

View of the Ramparts of Fort Moultrie, Charleston Harbor, S. C—from a Photograph by __ Luce, Esq.3

View of the Ramparts of Fort Moultrie, Charleston Harbor, S. C—from a Photograph by __ Luce, Esq.3

Old soldiers are credited with a fondness for fighting their battles over again, and perhaps I am no exception to the rule. Yet I have never troubled the public with any of my personal recollections. I have never felt a burning desire to do so. If I take a new departure now, it is not because I expect to be instructive; the public is already surfeited with instruction on the subject. If I can rescue from oblivion some of the more amusing incidents of those stirring times I shall be satisfied. They may have no historical value; yet the picture, when painted, would be a dreary composition without them. It would be a pity to deprive the future historian of any material that might add interest to his story. With this excuse for my new departure I approach my subject.

Pleasant as the undertaking appears to be, it is not easy. The moment one begins to parade his recollections on paper he loses all respect for them: they seem to be so silly, so trivial, so insignificant. He feels that people can have no interest in them, that they already know enough on the subject; that they have read accounts of it, more or less true, more or less romantic; that they have already formed their opinions, crowned their heroes, and closed the case. Then he remembers that they have gathered their information from a broad field: from able historians, public documents, and private notes. Is it any wonder that one should feel diffident in producing before such an audience his own starveling reminiscences? They have been gathered from no such broad field,—they are, they must be, narrow and insignificant as was the horizon which limited his view: mere relics from the lumber-room of memory,—the very ghosts of dead ideas, dusty and cobweby. To be sure they might be polished up, but that would ruin their reputation. Cobwebs have been known to impart respectability and flavor to very poor wine; let them cling to my story then. In their name I crave indulgence; they are my excuse for telling the story.

It was my fortune to be present at the opening scenes of the grand drama of the American civil war. There were but few of us on the Union side on that occasion, seventy odd I believe, but to save my life I could not now tell exactly how many. One would naturally think that in such a handful of men any one of the party would know pretty much all that occurred; yet I have to confess that I know very little, and that little is so abominably mixed up with self that I am ashamed of it. I might read up and prepare a presentable story, more comprehensive and in better form; but that would be wiping away the cobwebs, which I have decided not to do. So, uncouth and unconnected as the story may turn out to be, I shall confine myself strictly to what I find in my memory, facts and impressions the recollections of which have withstood the erosions of almost a quarter of a century. They were stored away without design; they have been preserved without effort; they are now reproduced without polish or paint, and I hold myself in no way accountable for their homely looks.

The rebellion began before the war did, and the war began before the first shot was fired. I had been stationed in Charleston harbor for some years prior to 1861, had made some acquaintances among the business men of the community, and had a fair opportunity of judging early in 1860 how the political wind was blowing. That the State would secede was never doubted after the disruption of the Democratic convention. Secession was referred to as a gratifying certainty, and war with the North was a pleasing possibility. Defeat was considered less likely than a second deluge. Cotton was king.

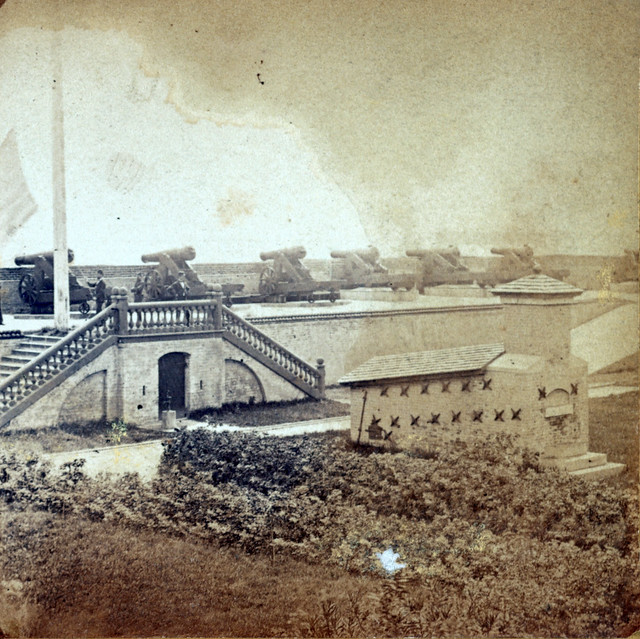

Fort Moultrie interior, August 18604

Fort Moultrie interior, August 18604

Fort Moultrie, where I was stationed, was a historic work. Its importance rested rather upon what it had been than upon what it was. It was an inclosed work, bastioned on the land side. Its water battery consisted of eight or ten 8-inch Bomford columbiads, mounted en barbette on wooden carriages. Its scarp was of brick masonry, and perhaps ten or twelve feet high. The land-front mounted 24-pounder guns and 8-inch howitzers. It was provided inside with barracks and quarters for two companies of artillery. The commandant’s quarters, hospital, commissary and quartermaster’s stores, and laundresses’ quarters were outside. It was one of the regular defenses of Charleston harbor, and for that purpose was fairly effective; but as against a domestic enemy it was worthless. The sand had drifted against its scarp wall to such an extent that cows, tempted by the grass which grew on its slopes, had no difficulty in jumping in, and soldiers of convivial and owlish habits had no difficulty, even when too far gone to jump, in rolling over the rampart in time for reveille. The rebel leaders no doubt felt that they could walk into Fort Moultrie whenever they wanted to, in spite of the seventy odd men which constituted its garrison.

The garrison consisted of two companies of the First Artillery and the regimental band. The companies were small, perhaps purposely kept so, numbering, if I remember rightly, about thirty men each. According to the organization, their strength should have been fifty-four, but yellow fever had played sad havoc among the men in 1858, and requisitions for recruits had remained unheeded. Hence the numerical weakness of the garrison.

The commanding officer was Lieutenant-Colonel John L. Gardner, First Artillery. Colonel Gardner was well advanced in years, but active, energetic, and perfectly competent. He was brave. His conduct during our yellow fever trial two years before proved that to the soldiers’ satisfaction; and they rarely make mistakes on that point. They had confidence in the colonel, and felt that the honor of the old flag was safe in his keeping. But he had been born in Massachusetts. To be sure, he would have been a stranger in his native State. His manhood had been spent in the service of his country, and mostly in the Southern States. He had no visible politics, and no perceptible prejudice against “the peculiar institution.” Still, his birth was against him at that time, and in that place. Then he was a religious man, and had a weakness for returning prodigals. He would rejoice over one reformed rascal more than over ninety and nine good soldiers who needed no reformation. He was the first officer I ever heard talking religion to his men. I remember the points of his speech on that occasion; they were few but forcible. It was Sunday; church call had sounded, and the men were paraded in accordance with an old army custom. The colonel approached, and the men felt they were in for a lecture. They had been neglecting their religious duties, and the colonel knew it. He said substantially, “I want to say a word. Men,—soldiers are men; and men are merely animals with a religion. Therefore soldiers must have a religion. There are only two religions,—Christianity and infidelity. Therefore soldiers are either Christians or infidels. Which are ye? March the men to church.” It was a short sermon, earnest, opportune, and well meant, but fruitless. It was the old story of the horse and the water-trough. The men were marched to the church door, declined to enter, and were marched back again. The colonel could not compel attendance. He could not cram the gospel down their throats, but he could compel them to listen to the Articles of War. This he did very frequently during the hour of divine service. The officer detailed to do the reading, who seemed to hate the whole performance as cordially as did the men, read in a rapid monotone, except when he ran across the words, “shall suffer death,” which he did very frequently. These he read with all the emphasis he could command, pausing for a moment when the dread penalty had been pronounced, and glancing furtively, but in vain, for some symptom of repentance among the constructive infidels whom he addressed.

The country was fortunate in having Captain John G. Foster in Charleston harbor at that time. Captain Foster was an officer of engineers, and disbursed the funds appropriated by Congress for the defenses of Charleston. He had quite a number of men, perhaps a hundred and twenty, at work upon Fort Sumter, which was still unfinished, and some more making repairs on Castle Pinckney. These workmen were principally from Charleston City, but some were from Baltimore. The rebel leaders doubtless believed that they would be “loyal to their State,” which was the fashionable way of saying they would be disloyal to the United States. The work they were doing for United States wages would, in the opinion of the rebels, ultimately be for the benefit of the rebel South. It must have been a gratifying spectacle, and a strong encouragement to those on the brink of rebellion, to see the purblind government building and arming works to be used against itself. But Captain Foster was not altogether blind. He set a large gang to work upon Fort Moultrie. It was the only work with a garrison in the harbor. In its then condition it was untenable. The rebels hoped it would remain so until they were prepared to attack it. They knew that no sane officer would attempt to defend a work that wouldn’t keep the cows out with such a handful of men, and confidently expected surrender when the demand was made. But Foster’s operations must have disturbed their dreams. The sand was cleared away from the scarp wall, new flank defenses were added at the salients, traverses were constructed, and many new and mysterious arrangements were made inside, all of which meant fight before surrender. Then, as if to add insult to injury, Colonel Gardner closed the gates against all civilians unprovided with a pass from him. These proceedings were the first unmistakable symptoms of resistance, the little cloud which advertised the deluge.

That we would have to fight in Fort Moultrie was no longer doubted by the men. Everything began to wear a warlike look. All soldiers were required to sleep inside the fort. Guards were strengthened,—in fact, the whole garrison was put on guard at night. Non-commissioned officers were posted as sentinels. The men were permanently assigned to the several batteries. Commanders were designated. Alarms were sounded by night and day as an exercise, and to test the vigilance and efficiency of the men; and very soon the garrison was in splendid condition and ready at any moment to repel an attack. If appearances were worth anything, the garrison would suffer a defeat before it would think of surrender. This was very displeasing to the rebel element, and the less cultivated among them could not conceal their displeasure. Crowds gathered daily opposite the gate to watch the warlike preparations. These were not of a reassuring character. The artillery exercises especially were suggestive. They consisted in practice with improvised hand-grenades and shell-torpedoes. The hand-grenades used were common shells with five-second fuses; the fuse was ignited by hand, and then the soldier had time to throw or roll the shell over the parapet before explosion took place. Some of the men became very expert in this practice. It was capital sport for the men, and had a wonderfully cooling effect upon the ardor of the spectators. Few among the latter would have volunteered for a forlorn hope with any kind of confidence. Yet the whole thing was brag. We kept no prepared grenades on hand, and none would have been thrown if an assault had been made on Fort Moultrie.

The shell-torpedo was also a scarecrow; it consisted of a ten-inch shell, loaded with a blowing charge, and provided with a fuse which ignited by being trodden on. It was buried, fuse up, some six inches under the surface; a piece of plank was laid over the fuse, and the whole covered with sand and raked smooth. To fire it some one struck over the plank with a long pole, and explosion resulted. It was intended to illustrate the danger of treading on forbidden ground. We were not annoyed by inquisitive strangers prowling around the work after that; they kept strictly to the public roads. Although there never was a shell-torpedo planted in earnest, they evidently believed the sand was full of them. Humbug is highly essential in war.

To the lay mind Fort Moultrie was becoming formidable. Even now they thought it could not be taken without bloodshed, and it was getting stronger every day. Colonel Gardner was an energetic fool. Could he not see that he would have to surrender anyhow? and might he not do it gracefully without bloodshed? But it was impossible to mistake his intentions. He evidently meant to fight until he was forced to surrender. He was too old to appreciate the situation. If he continued in command peaceable secession would be impossible. Peaceable secession was highly desirable. Colonel Gardner was an obstacle in the way; therefore Colonel Gardner must be removed.

Removing an old but active officer who was willing to serve was less easy then than now. There was no retired list to which he could be honorably transferred; and if he would neither get sick nor ask for leave of absence, nothing remained but summary removal. In this case the last method was inconvenient, unless it could be made to appear that it was done in the interest of the government. A report to that effect was necessary as a basis of action. So the Secretary of War sent an officer to inspect the work. I remember his arrival well. We all wondered what it meant; would it end in the withdrawal or reinforcement of the garrison? The officer sent was a captain then, but has since become better known as General Fitz-John Porter. He wandered about the work for two or three days and then returned to Washington. In a few days after Lieutenant-Colonel John L. Gardner was relieved from command of the post, and Major Robert Anderson was appointed in his place.

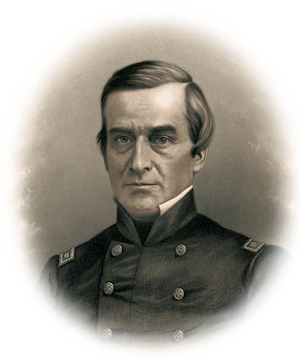

Major Anderson was a native of Kentucky. He was a fine, soldierly-looking man, with features clean cut as a cameo, and an expression and bearing which indicated a haughty, imperious disposition. Perhaps the soldier’s description of him is the best pen-picture that can be drawn,—“He looked like a thoroughbred.”

Major Anderson was a native of Kentucky. He was a fine, soldierly-looking man, with features clean cut as a cameo, and an expression and bearing which indicated a haughty, imperious disposition. Perhaps the soldier’s description of him is the best pen-picture that can be drawn,—“He looked like a thoroughbred.”

The men, although sorry to part with their old commander, took to the new one kindly from the first. I remember well the day he took command. He had been down at Colonel Gardner’s residence, which was outside the fort, and quite a crowd of citizens had collected in front of the main gate to get a glimpse of the new commander. As the major approached, the sentinel offered the appropriate compliment and salute, and the gates swung open for his admission. Acknowledging the sentinel’s salute, but declining the proffered compliment, he called for the commander of the guard, and directed that the gates be left open in future. Then, after hesitating a moment, he turned to the crowd and, with a courteous gesture, said, “Walk in, gentlemen, if you wish to. We have no secrets here.”

A new policy, as well as a new commander, was inaugurated at Moultrie that day. The gentlemen walked in, curious, but uncomfortable. They kept strictly to the brick walks. Their recollections of shell-torpedoes made them less inquisitive than they would have been. They saw little, and understood less, of what was going on. Yet to a certain extent the cat was out of the bag. The mounds of sand which their imaginations had made so formidable when concealed, were simple enough, and seemingly harmless enough, when seen. But why did Colonel Gardner close the gates? Why did the man with only sixpence in his pocket fight so hard with the highwayman? To hide his poverty.

The preparations for defense were continued with as much energy after Major Anderson’s arrival as before, only there was no concealment. Mystery no longer magnified our efforts. What we did was seen and judged by all who chose to enter. By and by we were almost ready, as far as labor and sand could make us so. We had overhauled our ammunition, counted our cartridges, and considered our wants. We needed many things. We needed men worst of all, but we knew we could not get any. If we were to stand a siege we needed more provisions,—we only had one month’s supply,—but we knew it would be useless to ask for them. Then we needed more friction-primers. We knew there were plenty in the arsenal over in Charleston, but they might as well have been at the north pole. If we asked for them in the regular way, we would only expose our weakness and destroy every hope of procuring the needed supply. The only way was to get them out of Charleston by stealth. An officer of the garrison took charge of the undertaking. He went to the city, in mufti, one day, and several soldiers who were on pass happened over on the same day, also in mufti. They met by chance at the arsenal. The officer anticipated no difficulty in getting the primers. It was getting them out of Charleston which constituted the difficulty. This he hoped to overcome by means of the soldiers. Each man could carry at least one thousand primers without attracting attention. There seemed to be no great difficulty about it, yet the scheme failed. The fact that disguised soldiers from Fort Moultrie were assembling at the arsenal got abroad in the city, and there was some trouble. At any rate, the officer and his party had to come home without the primers. We had some on hand. The failure of the expedition was not altogether ruinous, but it was very unfortunate for all that.

U.S. Arsenal, Main Building, Charleston, South Carolina5

U.S. Arsenal, Main Building, Charleston, South Carolina5

By this time South Carolina had seceded. The Palmetto flag floated everywhere except on Moultrie. We were virtually a beleaguered garrison without the formality of a declaration of war. We were watched by everybody during the day, and by an armed steamer with militia on board during the night. The time for us to be eaten up was evidently at hand. Prudence required that we should prepare ourselves for the sacrifice. There was but little that we could do except get rid of our impedimenta. We had a fine collection of women and children to dispose of. It was natural that we should desire to place them in safety. The chivalry of the South could not well object. So two large schooners were chartered to carry them to Fort Johnson. Two large schooners to carry the wives and children of a garrison of seventy odd men! It is a solemn and significant fact; and not more than a third of the men were married at that. The schooners arrived a little before dusk. After dark they were loaded. Everything eatable at the post was put on board. We were bound to see the women and children provided for. But what did they want with ammunition? Why was our store of powder surreptitiously slipped on board? Pat never inquired. It was Foster’s laborers that loaded the schooners, and they were not familiar with the external appearance of ammunition packages. Besides, they were disguised. Many an Irishman smoked his dhudeen in a comfortable way that night seated on a powder-barrel, and coolly knocked the ashes out on the chine in blissful ignorance of his danger. By daylight all the contraband of war was on board and stored below. The hatches were secured and the laborers dismissed. A detail of soldiers now appeared, and furniture began to arrive. Chairs, tables, boxes and bureaus, beds, mattresses and cradles were piled on deck. At last the women and the children marched on board, sad and tearful. A few hasty good-byes were said. An officer stepped on board. The lines were cast off, and our principal impedimenta were on the way to safety. “It was kind in the major to send an officer with them, though.” “Faith, and few commanders would have even sent a sergeant,” were remarks that might have been heard on the wharf after their departure. But then the speakers knew nothing of what was in the hold.

As amicable relations had been, to all appearances, permanently established between the gentlemen of South Carolina and the officers of Fort Moultrie, there was nothing strange in most of the latter being the guests of some of the former the day before Christmas.6 It was a little strange, however, that the officers should come home before sunset. It was said the major had been taken ill. Then our captain, a strictly temperate man, who, moreover, had not been at the party, and who never was known to make a bet, acted as if he had laid a large amount by way of a wager with some betting lunatic as to the amount of ammunition that the men could carry on their persons if they were to try. I do not mean it be understood as saying that he made such a bet, or that he said he had done so, only that the impression among the men was that he had. So to decide this imaginary bet, as the men thought, they were required to fall in at retreat roll-call loaded down with cartridges.

It may seem that we were mighty obtuse; but, so far as I know, not a man had the remotest idea that we were going to move. Everybody had made their minds up that the coming fight would be at Fort Moultrie. They knew nothing of the ammunition that had been shipped; and everything that had occurred indicated resistance and not removal.

Evacuation of Fort Moultrie by Major Anderson and the United States Troops7

Evacuation of Fort Moultrie by Major Anderson and the United States Troops7

The drums beat off retreat as usual, and the flag came down, but, instead of being chucked away in its box by the flag-staff, it was carefully folded up under the direction of an officer and brought down from the ramparts. Everybody knew then that something serious was in the wind, but not a word was spoken. Without a word, excepting those of command, the men were marched away, and as they left the fort the gates were shut. Without any effort at concealment, except that the arms were trailed, the men were marched to the front beach, where boats with muffled oars awaited them. They embarked, and the boats were headed for the guard-steamer, lazily lying at anchor in mid-stream. Were we going to capture her? No doubt dozens thought we were, for many hands stole furtively around to be assured about the bayonet being there, and ready to be fixed at a moment’s notice. Whatever was thought, nothing was said. Only the measured dip of the muffled oars disturbed the stillness, and that could hardly have been heard if it had not been seen. Discipline is invaluable at all times, but especially so in moments like these; one word might have spoiled the game. We passed close to the steamer. We could hear the songs and laughter of those on board. Many among us who had already braced their nerves for the assault found out that they were wrong. Sumter, and not the guard-boat, was our objective-point. Nerves were relaxed, eyes twinkled, faces melted into smiles; yet not a word. One danger was past, and another was approaching. The laborers in Sumter—rebels almost to a man—must be surprised. If they discovered our approach in time they could defeat our purpose; but they were as careless as the soldiers on the guard-boat. It was Christmas-eve [actually the day after Christmas8], and both parties were making a night of it. The laborers, or some of them at least, were playing “seven up” when the muzzles of half a dozen rifles appeared at the door. They got no chance to talk. “Come out of there, and be quick about it,” was all the sergeant said; but the muskets of his men were ready, and the soldiers only waited for the word. The sergeant was not there to answer questions. There was nothing for it but obey. The laborers turned out,—sulkily enough,—out of their snug, warm barrack, out of the fort, and saw the gates close behind them. The thing was done,—the transfer was made. Sumter was occupied; the garrison was safe. It was one o’clock in the morning, however, before it was thought wise to advertise the fact. Then three guns were fired from Sumter, and the four men left in Moultrie lit their torches; and the officers, with the women and children, cut loose from Johnson and made for Sumter. And the watches on the guard-boat found out they had been fooled; and a ruddy glare in the direction of Moultrie told them, and all who were awake in Charleston harbor that night, that Fort Moultrie was on fire.

Entry of Major Anderson’s Command into Fort Sumter on December 26, 18609

Entry of Major Anderson’s Command into Fort Sumter on December 26, 18609

There were four men left in Moultrie, and they had important work to do. Fort Moultrie with its armament complete was more than a match for unfinished Sumter with its guns unmounted. Therefore the armament of Moultrie must be destroyed. This was the work intrusted to the four men on that eventful night. As soon as the garrison had left the guns were spiked; and combustibles were piled around the wooden gun-carriages; and the old flag-staff was cut down; and all the war-like stores, as far as practicable, were destroyed. Then when the signal-guns were heard the torch was applied; and tongues of flames shot up and lighted up the bay; and our careless friend, the guard-boat, whistled the alarm; and Charleston awoke and sent a shower of rockets upward to the sky; and blue-lights burned; in short, there was a first-class Fourth of July celebration in Charleston harbor at one o’clock in the morning of Christmas-day [actually December 27].

The four men left in Moultrie did their duty well. They meant to have no failure in their work, and they had none. They remained in the fort until afternoon. Meantime, a large crowd collected in front of the entrance. The gates were shut, and a sentinel was pacing his measured beat as if nothing unusual were going on. They told him that the fort appeared to be on fire, and asked how many men there were within. But he made no reply. Then they crowded closer to the gate, and seemingly intended crowding the sentry off his post. They could no longer be ignored. The sentry with his bayonet-point scratched a line across the road, and said, “I’ll shoot the first man that puts his foot across that line.” They laughed at that at first, but by and by they lost their tempers some and cursed the sentinel. They said the fort was theirs, and they would enter when they chose. But no one put his foot across the line.

About 1 P.M. the sentry was withdrawn. The little wicket opened; the sergeant’s face appeared, and called the sentinel. The sentinel withdrew; the wicket was reclosed; and the mob yelled and threatened. Meantime, the four men hurried to the other side of the fort, jumped from the parapet, and made their way to Sumter. Such is the story of the destruction of the armament of Fort Moultrie, as told to me immediately after the event by those who did the work.

Sumter was hardly defensible when we got there. We had a very busy time for several weeks. Guns had to be mounted. Extra embrasures, which we had not men enough to defend, had to be bricked up. Then provisions were rather scarce for a siege. We had some, it is true. We had fallen heir to the rations of the workmen, in addition to those shipped from Moultrie. We could get along perhaps for two months, if it were not for the women and children. Then the Governor of South Carolina, perhaps to make us prodigal of the supplies we had, kindly permitted us to purchase in open market, in the city, one day’s rations at a time; that is, of fresh meat and vegetables. When that permission was withdrawn, which it was in due time, as a matter of course our troubles began. Then we had to beg. Not for bread,—we knew that would be useless,—but for permission to send away the women and children. This at-last was granted, and the siege began in earnest.

I shall only refer to a few incidents of the siege. Shortly after the departure of the women and children we were put on short allowance, which gradually became shorter, until it reached one cracker a day, and finally disappeared altogether. The only thing we had plenty of was salt pork, fat and rusty, a look at which was as satisfying as a ration. I have never had an appetite for pork since. But the men were cheerful as a rule; I heard no grumbling. They seemed to realize the situation, and were too busy or too patriotic to complain. And that reminds me that I have not disposed of the workmen whom we so unceremoniously turned out of doors on our arrival.

Men were too valuable to be thrown away. If any of the workmen were willing to cast in their lot with the garrison and fight for the honor of the old flag, the garrison would be thankful for their assistance. Captain Foster conducted the negotiations. The astonished workmen were huddled together on the wharf, trying hard to understand what had happened. Foster called them up, one at a time, to the wicket in the main gate, and put to each the momentous question, “Are you willing to share the fortune of this garrison and fight in defense of the old flag?” If the answer was yes, and the man seemed honest about it, he was taken in; if he said no, he remained outside.

Quite a number of them elected to remain with the garrison, among them the foreman bricklayer, the foreman carpenter, and the foreman blacksmith. The bricklayer was a Baltimorean, a bright, active, intelligent man, and thoroughly loyal. He at once took charge of the masonry-work essential to the defense of the fort by so small a garrison. Fortunately, there was plenty of building material in the fort. The embrasures of the second tier were all bricked up. There were no guns mounted on that tier. About three-fourths of the embrasures on the lower tier were also bricked up; not because there were no guns there, but because we had no men to defend them in case of assault. A breast-high wall was also built across the main sally-port inside the gate, to facilitate the defense of that entrance when the gates were demolished. In short, the boss bricklayer had plenty to do, and his services were invaluable. When the bombardment began he acted as a cannoneer, and was the only man seriously wounded during the fight.

The boss carpenter was also invaluable. He was intelligent, a capital workman, and intensely loyal. His usefulness was not confined to his trade; he was handy at anything.

The boss blacksmith was a character. He was, I think, an Englishman, and must have weighed over two hundred and fifty pounds when he joined himself to the Sumter garrison. He was a skillful workman, of course, or he would not have been boss of his department, and did valuable service in the defense; but toward the close of the siege he had a terrible time with his appetite. Yet he was good-natured throughout, was a prime favorite among the men, and never expressed a regret at having joined the garrison. He fought famously during the bombardment, and left Fort Sumter a comparatively thin man.

Those workmen who declined to cast their lot with the garrison were sent to Charleston, the barge making, I think, two or three trips for the purpose.

We had been a week without marketing. It was well known to our adversaries that we were suffering, and many believed we were starving. That they would have compassion on us we had no right to expect, and didn’t expect. In their frequent trips by steamboat to Morris Island, with material for the batteries they were building, they passed as close to Fort Sumter as practicable. They could see the gaunt-looking sentinels pacing their weary round in the air, sixty feet above the water, and seemingly expected them to say something. Perhaps they expected every trip to be hailed and asked for transportation to Charleston by the Sumter garrison, starved into mutiny. But our men were forbidden to talk. The eager looks of expectation directed toward them from the decks of the passing steamers, and which undoubtedly were looks of sympathy, were misunderstood, and deemed an impertinence by the sentinels. Unable to answer in unadorned Anglo-Saxon without disobedience, and still determined to be even with the “Johnnies,” the sentinels, when no officer was around, resorted to a very expressive pantomime, which seemed to give them great satisfaction, and never failed to make the other fellows impolite. I have seen a sentinel, who believed himself unobserved on such an occasion, with his musket balanced on his shoulder, the thumb of one open hand at his nose, the thumb of the other touching the little finger of the first, and an expression on his face which would have broken the heart of Grimaldi if he had seen it; and I knew that a steamer was passing the fort within hailing distance, and he was conversing with the men on board. Then let some one in authority make his appearance, and the change in that sentinel would be miraculous,—the musket and the man would straighten up simultaneously, and the latter would be ready to swear that he had held no conversation with the steamboat.

It was generally believed among outsiders that many of the garrison would desert if they only had the chance. From their stand-point, and with their ideas of patriotism, the belief was not unnatural. The investigation of a homicide which had occurred some six months before on Sullivan’s Island gave them an opportunity to put this idea to the test. The case was before the grand jury, and some six or eight Sumter soldiers were subpœnaed as witnesses. The subpœnas were brought over under a flag of truce and delivered to the major. Sure enough, when the day appointed came, the men were sent to Charleston. They were there, I think, two days. When they returned-which they all did—they informed me that they had been treated splendidly while they were in the city; had had plenty to eat and drink and tobacco “till they couldn’t rest,” and nothing to pay; that they had been permitted to go where they pleased and buy what they liked; in short, treated like gentlemen until they announced their determination to go back to Sumter. Then they were kept under surveillance by the police, and when they went on board the boat which had been sent for them they were searched, and all the eatables, drinkables, and tobacco which they had been permitted to purchase were taken away.

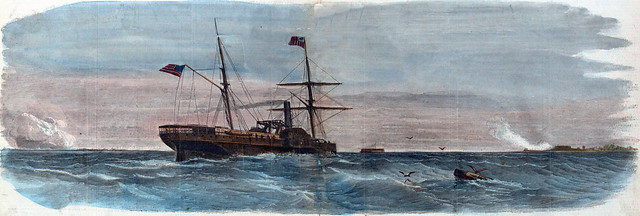

The Steamship Star of the West, with Reinforcements for Major Anderson, Approaching Fort Sumter—The South Carolinians Firing at Her From the Batteries of Morris Island and Fort Moultrie10

The Steamship Star of the West, with Reinforcements for Major Anderson, Approaching Fort Sumter—The South Carolinians Firing at Her From the Batteries of Morris Island and Fort Moultrie10

The episode of the “Star of the West” was a very exciting incident while it lasted. The strange steamer was first seen off the bar early in the morning. What she was doing there was a mystery. She seemed to be at anchor. Presently she got under way and stood in toward the harbor, taking the Morris Island channel, and flying a United States flag of unusual dimensions. As she approached the excitement increased, and the probability of enjoying a square meal in the immediate future brightened the eyes of many of the garrison. At length a puff of smoke from Morris Island, then another and another in quick succession, told us, even before the sound had reached our ears, that the rebels had a battery around there, and were firing on the steamer. The long roll was beaten, and every man sprang to his gun with a will. The guns already loaded were pointed on the rebel battery in an instant, and the hands which held the lanyards trembled with eagerness for the word to fire. But the word was not given. The major had some kind of a consultation with some of his officers; they were not all there. The consultation was held in the laundry. Of course I know nothing of what was said at the conference. The opinions I formed were based upon the conduct of Captain Foster. He left the laundry in a hurried manner, smashing a rather seedy silk hat, which indicated a condition of mind bordering on lunacy, seeing that that silk hat was the only head-gear he possessed. He habitually wore citizen’s dress, and having on this occasion buckled on a sword over an ordinary walking coat, was a figure calculated to attract observation in a garrison. I knew that Foster was for fighting, and judged from appearances that the major wasn’t.

The affair of the “Star of the West” gave rise to a lengthy correspondence between Major Anderson and the Governor of South Carolina, which was no doubt high-toned and honorable, if not a little bombastic; but nothing came of it, not even an additional cracker to our contracted ration.

Firing at the Schooner Shannon, Laden with Ice, From the Battery on Morris Island, S. C. April 3, 1861

Firing at the Schooner Shannon, Laden with Ice, From the Battery on Morris Island, S. C. April 3, 1861

Another amusing incident was the visit of a Yankee schooner. The captain had lost his reckoning. He had no idea where he was, except the general one that he was somewhere on the Southern coast. He had been some time at sea, and knew of no unpleasantness at any of the Southern ports. He was loaded with ice, which may account for his coolness, and was bound from Boston to Savannah, Georgia. Having arrived off the harbor, which he mistook for the mouth of the Savannah River, he set his ensign proudly enough, and made for the harbor. As soon as he came within range, the “Star of the West battery, as we had named it, treated him and his flag to a regular broadside. This astonished him, no doubt, but did him no material injury. He was near enough now for us to see all his movements with a glass. He was evidently scared, and just as evidently puzzled. He rushed to his ensign halliards and gave them a savage tug or two, looking at the same time in the direction of the battery in a nervous, angry manner, the same as to say, “Don’t you see that flag, the ensign of the universal Yankee nation? What do you mean?” when bang! came a second broadside from the “ Star of the West,” and a first one from Fort Moultrie. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

The bewildered skipper seemed to give it up. He hauled down his ensign, cast anchor, and commenced mending his mainsail, through which a couple of round-shot had found their way. He was visited immediately by a boat from the rebel batteries, and also one from Sumter. When our boat returned, the men said that a madder American would be hard to find than was on board that schooner. He left for Savannah that night.

Still another incident which created quite an excitement happened in this way. The rebel batteries were now finished, and practicing every day. Sometimes the guns were shotted, and the targets aimed at were the buoys to the right or left of Sumter; but more frequently the practice was with blank cartridge, to perfect the men in the manual and accustom them to the racket of the guns. Well, one day they were having practice with blanks from Stevens’s Battery. Stevens’s Battery was the nearest rebel work to Fort Sumter, being twelve hundred yards distant. It was an ironclad battery, and mounted three guns, bearing upon the gorge wall, the main gate, and the wharf of Fort Sumter. The post of sentinel No. 1 was on the wharf, and the sentinel was an ex-officer of the Prussian army, as he was very fond of telling his friends. He may have had more rank in the Prussian army than he had in the American, but I defy him to have had more dignity. On post, he was the impersonation of military intolerance. He seemed to look down on all mankind, and feel himself a superior being. Presently a solid shot came screaming from Stevens’s Battery, and struck the coping of the wharf immediately in front of the main gate, smashing a large block of granite to “smithereens.” The sentinel was within a few feet. He halted, gazed at the demolished rock for an instant, seemed to realize the situation, threw his arms to port, and called loudly, “Sergeant of the guard, No. 1!” When that functionary appeared, without moving one unnecessary muscle, the sentinel pointed with his head in the direction of the demolished stone, reported “round-shot,” brought his musket to a “right-shoulder shift,” and resumed walking his post. Although the sentinel remained cool as a cucumber, the garrison was thrown into commotion. The long roll was beaten at once, and the batteries were manned; but before anything further could be done a white flag appeared on the offending battery, and a boat put out from it similarly equipped and pulled for Sumter. It brought the culprit, an impatient rebel, who, having grown weary waiting for the war to begin, had surreptitiously slipped a solid shot into his gun. The rebel officers offered to turn him over to Major Anderson for punishment, but the major declined to receive him, saying they might punish him themselves if they thought it necessary. I doubt if they did. The culprit certainly did not expect it. He looked as if he felt himself upon the very pinnacle of fame.

There was no end to our devices for defense, and some of them were ludicrous enough. We could see our adversaries by the thousand drilling on the beach over against us every day, and the chances that we would have with such a multitude if they ever assaulted us forced themselves on our consideration. That the main gate would be battered down early in the action could not be doubted, and if an assault were attempted it would be at that point. Of course the enemy must come in small boats, but they might do that under cover of darkness. Then they must land and form some kind of a column before they could charge any fairly-defended breach with success. The wharf was the only fit place for such landing and formation. The wharf, therefore, should be subject to a grape and canister fire. There were no embrasures in the gorge wall, and the guns, en barbette sixty feet above the water, could not be depressed so as to be effective. To remedy this, part of the parapet was cut away in front of two 24-pounders which could be brought to bear upon the wharf. The kind of projectile to use in these guns was the subject of much debate. At last it was decided to load them with a stand of grape and a bag of broken stones. These filled the gun nearly to the muzzle, and much curiosity as to the effect of such a charge was experienced. To satisfy this curiosity it was determined to fire one of them off.

The night before this trial was made I was on guard. In making my rounds, just after sunset, I found a ten-pound cartridge which had been carelessly overlooked when those spread out to dry in the sun had been taken in. It might rain before morning, and it was too late to get into the magazine; so I took out the tompion of one of the 24-pounder guns, crammed in the cartridge, and replaced the tompion, intending to take it out again in the morning. Of course I forgot; and the gun was the one selected for the experiment. I was up there myself, and very much interested in the result. The tompion was removed, the gun was aimed and depressed, and then fired. It was a capital shot. The surface of the water was churned into foam all around the wharf, but the gun behaved in an unaccountable manner. There was an unusual amount of smoke. Part of the parapet was blown away, and the gun recoiled to and over the counter-hurters, and then turned a kind of hand-spring to the rear, to the amazement of the gunners and the officer in charge. Just as she was on the turn, I remembered the cartridge. The officer in command charged No. 2 with having failed to remove the tompion. This he easily refuted by producing the tompion. Then science was appealed to. Paper, pencils, and formulæ were produced, and much figuring was indulged in. This soon disclosed the cause of the disaster; the charge should have been diminished. Everybody was , satisfied with the solution, and I thought it would be a pity to spoil such a fine demonstration. At the same time, I was not convinced of its correctness.

Another laughable device was known as “Wittyman’s cheval-de-frise.” Wittyman was a kind of carpenter. He was a German by birth, and had never mastered the English language sufficiently well to understand technical descriptions. The captain of Wittyman’s company was convinced that the fort could be successfully assaulted, after the gate was battered down, by landing parties all around the work on the five or six feet of rip-rapping between the water and the foot of the scarp, and then rushing round simultaneously to the gate. To prevent the rushing, he proposed to place a cheval-de-frise across the rip-rapping at each end of the gorge wall. So he sent for Wittyman, and ordered two chevaux-de-frise. Wittyman knew no more about chevaux-de-frise than he did about parallelopipedons. Explanatory descriptions and illustrations were now in order. The captain was a deft draughtsman, and Witty man soon got an idea; that it was a wrong one was not immediately apparent. He gave it bodily form and placed it in position, such as it was. I shall not attempt to describe it. Suffice it to say that it was a source of amusement to the garrison during the siege. Whenever a man felt particularly hungry or specially blue, he would step around and take a look at Wittyman’s masterpiece, and he was sure to forget his misery in roars of laughter. Nor was that the only good effect it had; there is no telling how much influence it had in preventing an assault. It puzzled the rebels very much. Not a steamer or small boat passed the fort but every glass on board would be leveled at the nondescript. And they never found out what it was. After the fighting was all over, some rebels, who expressed a wish to see the corner which was so nearly breached, and were told they might go round and look at it, hesitated a moment, and glancing furtively at Witty man’s production, remarked, “It’s mined, ain’t it?” They were assured it was not, but the nondescript was too much for their curiosity: they didn’t go. Some of the men, probably Wittyman himself, unwilling that the mysterious defense should become known to the enemies of his country, soon afterward, removed it and threw the fragments into the water.

Our experience with hand-grenades at Moultrie had been so satisfactory that we developed the idea at Sumter, and made grenades an important feature in the defense. Sumter was admirably adapted to their use. We prepared and distributed large numbers of them about the work, principally 10-inch and 12-pounder shells. The larger shells were intended to be used from the parapet, and the smaller from the loopholed windows in the gorge wall. We had improved upon the Moultrie idea. Instead of using time fuses, which would be impracticable in action, we used lanyards and friction-primers. The shells were loaded with heavy bursting charges, and wooden plugs were driven in the fuse-holes ; gimlet-holes were then bored in the plugs and friction-primers inserted. Lanyards of spun yarn or marline, fifty-five feet long, were fastened at convenient intervals on the parapet, and prepared grenades were stowed under a convenient bombproof shelter. To throw a grenade, it was lifted on the parapet, the lanyard was hooked into the eye of the primer, and the shell was permitted to roll over; it descended the length of the lanyard, when the primer was fired and the shell exploded, just five feet above the ground. It would be difficult to conceive of a simpler or more destructive weapon for repelling an assault; we tried several, and they worked admirably. The smaller grenades were similarly prepared. They were stored away in the back casemates along the gorge wall.

In the early days of our sojourn in Sumter it was pleasant to see little children around; but it was not always free from danger, as the following incident will show. One day a great racket was heard in an empty upper room; it had been going on for some time, and seemed to be getting more boisterous. At last somebody went up to see what was going on. He found three or four children there, having a famous time rolling improvised ten-pins. The game, however, had to be stopped. The balls they were rolling were 12-pounder shells, loaded, primed, and ready for use as hand-grenades.

I shall never forget these shells. After the firing was over, the grenades were still on hand; not one had been used, as no assault had been made. For some reason or another the major did not wish the rebels to get the idea of the grenades. He could not honorably throw them overboard, so he ordered the primers to be drawn. To draw the primer from a loaded shell is about as dangerous as to extract the fangs from a rattlesnake. Yet we had to do it, and did do it. It would be difficult to hire men to do that kind of work.

The barrel-grenade was a device similar to the shell-grenade. It consisted of a barrel filled with stones broken to the size of road-metal, having a demijohn or canister containing a large charge of powder in the centre. The barrel was headed up, and looked harmless enough. It was fired by a friction-primer and lanyard, as described for the shell-grenade. Only a few barrel-grenades were prepared. We never tried but one as an experiment; it worked splendidly.

The rebels had an idea that Sumter was mined all over, and that we could blow it out of existence at pleasure. This idea arose out of a misinterpretation of observed facts. In fortifying against assault, we had observed that the sills of the embrasures were less than five feet above the rip-rapping. Parties were therefore set to work to excavate pits in front of the embrasures, some two or three feet deep. This operation was observed and misunderstood by the rebels: they supposed we were planting mines in front of the scarp.

As a matter of fact, there were only two mines planted at Sumter, and they were in the wharf. As already stated, the wharf was the most likely muster-ground for an assaulting column. If the rebels should determine to assault, and should land on the wharf, which darkness might enable them to do, to be able to blow them out of existence in a moment would be a manifest advantage to the defense. Consequently two pits were dug in the wharf,—which was of masonry, filled in with rubbish, and paved,—one near each end, and a five-gallon demijohn filled with powder was placed in each. A wooden trough, containing the lanyard and a powder-hose, connected the mines with the interior of the work under the wharf pavement. The lanyard was attached to the eyes of primers inserted in gimlet-holes bored through the stoppers of the demijohns, so that a single pull fired both mines simultaneously. The powder-hose was an auxiliary arrangement intended for use if the primers should fail. It terminated in a well about two feet deep just inside the main gate. The well was covered with a large flat stone, to guard against accidents. The lanyard, after entering the fort, divided into many branches leading to various points within the work. As no assault was made, we had no opportunity of testing the efficiency of our mines, and during the excitement of the bombardment they were almost forgotten.

In this connection a rather touching incident occurred. The bombardment was over. The barracks were still on fire, and sentinels were posted to keep over-curious Carolinians at a distance. There were thousands of them, in all kinds of craft, from steamboats to canoes, around the fort; but none were permitted to land. Our old acquaintance the ex-Prussian officer was again on post,—the same post on the wharf. He was in full uniform, and, as usual, fully impressed with the dignity of his position; in fact, rather more than usual, for his bearing had a heroic element in it hard to account for. He was hungry, we all knew that, and tired and weary, as we all were; for he had just had thirty-six sleepless hours of the hardest kind of work. Yet there he was, stately as a guardsman, and evidently happy. His orders were to keep everybody away from the wharf; they must not be permitted to approach it within two hundred yards. It was some time before we found out the cause of his elation. We had all forgotten that the wharf was mined; but he had not. He was on the post of danger, and he knew it. There were some three feet of live coals on the top of the stone which covered the free end of the powder-hose. The gallant Prussian knew that fact too, and supposed that he was posted there to see that people kept far enough away to escape destruction when the wharf blew up. It was not for him to remind his officer that there was a sleeping volcano under his feet. He was a soldier, and knew how to obey. Poor fellow! he was fond of beer, and quarrelsome in his cups, but God help the heart that cannot warm to such a man.

Unanimous as the people of South Carolina are supposed to have been in favor of secession, there were some loyal men among them. I remember one specimen, who, although Irish by birth, had spent his best years in the State. He was now hard on to sixty years of age, and fairly well off for a man of his station in life. He was a drayman and owned quite a number of teams, which he let for hire. When Captain Foster commenced work on Fort Moultrie a good deal of hauling had to be done, and McInerry, the drayman, willingly let his carts for the purpose. This displeased the rebels, and a committee waited upon him and demanded that he withdraw his teams. The committee reminded him that he was a citizen of South Carolina, and that patriotism demanded that he should not help the enemies of his State.

“A citizen of South Caroliny is it?” replied the drayman. “Faith, and do ye suppose I crassed the broad Atlantic to become a citizen of only one Shtate?”

Of course McInerry’s motives may not have been unmixed with mercenary considerations in that transaction, but the following is believed to be pure. There was a tobacco famine in Sumter. A piece of tobacco was almost worth its weight in gold. This condition of ours had got abroad in some way, or lovers of the weed had guessed at it, and one generous donation was received from a leading manufacturer in New York. But that supply was exhausted, and we were as badly off as ever again. One Sunday a small boat was observed leaving Sullivan’s Island, and coming in the direction of Sumter. It had no white flag, and contained only three men. When it got within five hundred yards of the fort it was hailed by the sentinel and ordered off, a shot being fired in front of it as a warning. The boat stopped, and the figure in the stern-sheets commenced gesticulating violently, and no doubt shouting, although we could not make out what he said. At last he seemed to give it up. He ceased gesticulating and sat down. Then some inexplicable proceedings were indulged in, and presently a large white flag was displayed, and the rowers resumed pulling toward the fort. The sentinel reported “Flag of truce approaching,” and the officer of the day ordered a boat away to receive it. But the flag of truce was too quick for him. While he was yet talking it came sweeping around the corner of the fort, and in an instant had hold of the wharf with a boat-hook. The officer of the day was furious at this irregular proceeding. He ordered the boat to cast off at once, on pain of being fired into. “Fire away if ye loik, and divil a hair I care!” said McInerry, for he it was in the stern-sheets of the boat. “Do ye suppose that afther ruining my Sunday shirt by tearing the tail aff for a white flag, that I’m going to be driven away like a dog without givin’ the by’s the tobaky ?” Meantime, he was throwing plugs of tobacco ashore to the men. After distributing in this way a good armful of navy plug he dropped away, without waiting for thanks, and the officer of the day promptly withdrew, in order that the men might have an opportunity of expressing themselves without committing a breach of discipline in his presence. This they did with a will, and many hearty cheers were sent after the generous and loyal Irishman, who had risked his life and ruined his Sunday shirt on their behalf. Poor McInerry! I saw him in 1872 sweeping the streets of Charleston.

-

- Chester, James. “The First Scenes of the Civil War.” The United Service. A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs. Vol.10, no. 5, May 1884.

- James Chester

- Born February 10, 1834, in Scotland

- Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment, December 1, 1854-April 17, 1863, private, corporal, sergeant, and first sergeant

- 1854-1856, Fort Monroe, Virginia

- 1856-1857, campaign against Florida Indians

- 1858-1860, Fort Moultrie, South Carolina

- 1861, Defense of Fort Sumter

- 1861-1862, Shenandoah Valley and Peninsular campaigns; commanded an artillery section at battles of Glendale, Malvern Hill, and Second Bull Run, Va., Antietam, Md. and Fredericksburg, Va.

- April 17, 1863, Brevet Second Lieutenant, 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment

- commanded battery at Chancellorsville; Va. commanded artillery section at Aldie, Middletown, Upperville, Va.

- July 3, 1863, Brevet First Lieutenant, U.S. Army

- Gettysburg, Pa., Shepherdstown, Va.

- Monument on the battlefield to Barreries E. & G.:

“July 3 One section under Lieut. James Chester was ordered to Second Brigade Third Cavalry Division and took position west of the Low Dutch Road and with Brig. General Custer’s Second Brigade Third Division Cavalry Corps was hotly engaged in repelling the attack of Major General Stuart’s Confederate Cavalry Division. The one section under Lieut. Ernest L. Kinney remained near the Hanover Road.

- Acting Assistant Adjutant General, 2nd Horse Artillery Brigade

- Major General P. Sheridan’s campaigns with Army of the Potomac and Shenandoah Valley, Va.

- August 25, 1864, Brevet Captain, U.S. Army

- Wounded at Kearneysville, Va.

- January 14, 1865, First Lieutenant

- September 1865, Joined company at Raleigh, NC

- October 20, to December 14, 1865, Aide-de-Camp to General Hardin

- December 1865 – April 1867, Acting Assistant Inspector General, Military Command of North Carolina

- Other roles and places:

- post adjutant, acting assistant quartermaster, and assistant commissary subsistence at Hilton Head, S. C.

- commanded battery at Ft. Pulaski, Ga.

- U. S. Artillery School

- commanded battery at Charleston, S. C.

- Ft Hamilton, N. Y.

- Military science professor at Iowa State University

- Assistant engineering instructor at U. S. Artillery School, Fort Monroe, Va.

- Engineering instructor at U. S. Artillery School

- Aide-de-Camp to Brevet Maj. Gen. G. Gotty

- June 7, 1897, Major

- February 10, 1898, retired

- Died, May 27, 1903, Washington, D.C.

- A 3-gun coastal gun battery at Fort Miley, San Francisco County, California, was named after Major James Chester

- Image from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 5, 1861; Special handed-tinted off-prints were also sold separately from the newspaper. Numerous originals are held today by public institutions and in private collections.

- This is the right side photo from a stereograph card. As part of… efforts to record “the most accurate stereoscopic views of places in and around Charleston” during the summer of 1860, the photographer James M. Osborn visited Fort Moultrie—whose dawn flag-ritual was obligingly recreated for him, even though this image’s shadows would suggest that it was actually taken around noon (possibly staged thanks to the participation of Capt. Abner Doubleday, senior officer resident within the fort). Two soldiers and two officers can be faintly discerned recreating this ceremony, presumably at its usual spot at the top of the main stairs.

- 1860s images of the “Charleston Arsenal” are invariably images of the old Charleston Arsenal which, at the secession of South Carolina was the home of “The Citadel,” a military college. The federal arsenal was about 3/4 mile from The Citadel. This image is derived from a 1963 Historic American Buildings Survey photograph. The only structure remaining from the 1860 arsenal is St. Luke’s Chapel, renovated in the 1880s from the former artillery shed.

- The troops’ evacuation of Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter actually occurred on December 26. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported the event as occurring on Christmas Day in its January 19, 1861 edition. In his Reminiscences of Forts Sumter and Moultrie, Captain Abner Doubleday identifies the date as December 26 as does Major Anderson in his official report to Adjutant General of the U.S. Army Samuel Cooper dated December 26, 1860—8 p.m.

- The original version of this image was in the January 19, 1861, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, captioned “Evacuation of Fort Moultrie by Major Anderson and the United States Troops on Christmas Night, 1860 —The Troops Conveying Powder and other Stores in Sloops to Fort Sumpter (sic).” The color version is one of the special handed-tinted off-prints that were also sold separately from the newspaper.

- See note 6.

- Harper’s Weekly, January 19, 1860

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, January 19, 1860. This color version is one of the special handed-tinted off-prints that were also sold separately from the newspaper.